Physics and Mathematics

Angular Momentum and Moment of Inertia

1. Introduction

Just as linear momentum measures the quantity of motion in linear dynamics, angular momentum measures the quantity of rotational motion in rotational dynamics.

It is a vector quantity that depends on both the rotational speed and the distribution of mass relative to the axis of rotation.

2. Definition

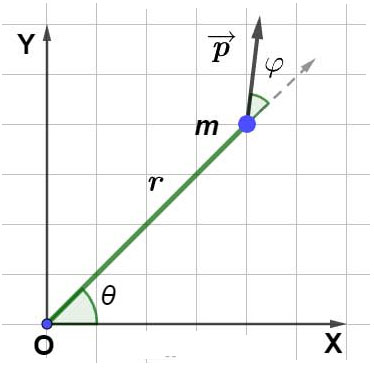

The angular momentum (L) of a particle with respect to a point (usually the axis of rotation) is defined as:

[ \vec{L} = \vec{r} \times \vec{p} ]

where

- [ \vec{r} ] is the position vector of the particle from the axis, and

- [ \vec{p} = m \vec{v} ] is its linear momentum.

3. Magnitude of Angular Momentum

The magnitude is given by:

[ L = r p \sin \theta ]

where [ \theta ] is the angle between [ \vec{r} ] and [ \vec{p} ].

If the motion is circular and [ \theta = 90° ]:

[ L = m v r ]

4. Angular Momentum of a Rotating Rigid Body

For a rigid body rotating with angular velocity [ \omega ] about a fixed axis:

[ L = I \omega ]

where [ I ] is the moment of inertia about the axis.

5. Direction of Angular Momentum

The direction of [ \vec{L} ] is perpendicular to the plane of rotation, determined by the right-hand rule — curl your fingers in the direction of rotation, and your thumb gives the direction of [ \vec{L} ].

6. Units and Dimensions

- SI Unit: [ \text{kg·m}^2\text{/s} ]

- Dimensional Formula: [ M L^2 T^{-1} ]

7. Relation Between Torque and Angular Momentum

From Newton’s second law for rotation:

[ \vec{\tau} = \dfrac{d\vec{L}}{dt} ]

This is the rotational equivalent of [ \vec{F} = \dfrac{d\vec{p}}{dt} ] in linear motion.

If [ \vec{\tau} = 0 ] (no external torque), then [ \vec{L} ] remains constant — angular momentum is conserved.

8. Law of Conservation of Angular Momentum

If no external torque acts on a system, its total angular momentum remains constant:

[ \vec{L}\text{initial} = \vec{L}\text{final} ]

This principle explains many physical phenomena — such as a skater spinning faster when pulling in arms or a collapsing star spinning rapidly.

9. Analogy with Linear Motion

| Linear Motion | Rotational Motion |

|---|---|

| Linear Momentum: [ p = m v ] | Angular Momentum: [ L = I \omega ] |

| Force: [ F = \dfrac{dp}{dt} ] | Torque: [ \tau = \dfrac{dL}{dt} ] |

| Conservation of Linear Momentum | Conservation of Angular Momentum |

10. Examples of Angular Momentum Conservation

- A diver tucking in mid-air spins faster.

- A planet moving closer to the Sun speeds up (Kepler’s second law).

- A spinning neutron star accelerates its spin after collapse.

- A figure skater pulls arms inward to increase spin rate.

11. Practice Questions (with Solutions)

Practice 1. A solid disc has mass [2.0 kg] and radius [0.30 m]. If it rotates at angular speed [10.0 rad/s], find (a) its moment of inertia [I], (b) its angular momentum [L], and (c) its rotational kinetic energy [K].

Solution:

(a) Moment of inertia for a solid disc about its central axis: [I = \tfrac{1}{2} M R^2].

Substitute values: [I = \tfrac{1}{2} × 2.0 × (0.30)^2].

Compute: [(0.30)^2 = 0.09]. Then [\tfrac{1}{2} × 2.0 × 0.09 = 1.0 × 0.09 = 0.09].

So [I = 0.09 \ \text{kg·m}^2].

(b) Angular momentum: [L = I ω].

[L = 0.09 × 10.0 = 0.90].

So [L = 0.90 \ \text{kg·m}^2\text{/s}].

(c) Rotational kinetic energy: [K = \tfrac{1}{2} I ω^2].

[K = \tfrac{1}{2} × 0.09 × (10.0)^2]. Compute: [(10.0)^2 = 100]. Then [\tfrac{1}{2} × 0.09 × 100 = 0.5 × 9 = 4.5].

So [K = 4.50 \ \text{J}].

Practice 2. A figure skater has moment of inertia [I_1 = 4.00 kg·m^2] while spinning at [ω_1 = 2.00 rad/s]. She pulls her arms in so that her moment of inertia becomes [I_2 = 1.50 kg·m^2]. Find (a) her new angular speed [ω_2], and (b) the change in rotational kinetic energy [ΔK].

Solution:

(a) Angular momentum is conserved (no external torque): [I_1 ω_1 = I_2 ω_2].

Solve for [ω_2]: [ω_2 = (I_1 ω_1) / I_2].

Substitute: [ω_2 = (4.00 × 2.00) / 1.50]. Compute numerator: [4.00 × 2.00 = 8.00].

[ω_2 = 8.00 / 1.50]. Compute: [8.00 ÷ 1.50 = 5.333… = 16/3].

So [ω_2 = 5.333\overline{3} \ \text{rad/s}].

(b) Initial rotational energy: [K_1 = \tfrac{1}{2} I_1 ω_1^2].

[K_1 = 0.5 × 4.00 × (2.00)^2]. Compute: [(2.00)^2 = 4.00]. Then [0.5 × 4.00 × 4.00 = 0.5 × 16.00 = 8.00].

So [K_1 = 8.00 \ \text{J}].

Final rotational energy: [K_2 = \tfrac{1}{2} I_2 ω_2^2]. Use exact fraction for clarity: [ω_2 = 16/3], so [ω_2^2 = (16/3)^2 = 256/9].

[K_2 = 0.5 × 1.50 × (256/9)]. Compute: [0.5 × 1.50 = 0.75]. Then [0.75 × 256/9 = (0.75 × 256) / 9].

Compute numerator: [0.75 × 256 = 192.0]. Then [192.0 / 9 = 21.333\overline{3}].

So [K_2 = 21.333\overline{3} \ \text{J}].

Change in energy: [ΔK = K_2 – K_1 = 21.333\overline{3} – 8.00 = 13.333\overline{3}].

So [ΔK = 13.333\overline{3} \ \text{J}] (the extra energy comes from the skater doing internal work while pulling in arms).

Practice 3. A particle has position vector [\vec{r} = (0.20,\,0.30,\,0.00)\ \text{m}] and linear momentum [\vec{p} = (1.50,\,0.00,\,0.50)\ \text{kg·m/s}]. Compute the angular momentum [\vec{L} = \vec{r} × \vec{p}] (vector and magnitude).

Solution:

Cross product components: [\vec{L} = (L_x, L_y, L_z)] with

[L_x = r_y p_z – r_z p_y]. Here [r_y = 0.30], [p_z = 0.50], [r_z = 0.00], [p_y = 0.00].

[L_x = 0.30 × 0.50 – 0.00 × 0.00 = 0.15 – 0 = 0.15].

[L_y = r_z p_x – r_x p_z]. Here [r_z = 0.00], [p_x = 1.50], [r_x = 0.20], [p_z = 0.50].

[L_y = 0.00 × 1.50 – 0.20 × 0.50 = 0 – 0.10 = -0.10].

[L_z = r_x p_y – r_y p_x]. Here [p_y = 0.00].

[L_z = 0.20 × 0.00 – 0.30 × 1.50 = 0 – 0.45 = -0.45].

So [\vec{L} = (0.15,\,-0.10,\,-0.45)\ \text{kg·m}^2\text{/s}].

Magnitude: [|\vec{L}| = \sqrt{(0.15)^2 + (-0.10)^2 + (-0.45)^2}]. Compute squares: [0.15^2 = 0.0225], [0.10^2 = 0.0100], [0.45^2 = 0.2025]. Sum: [0.0225 + 0.0100 + 0.2025 = 0.2350].

[|\vec{L}| = \sqrt{0.2350} ≈ 0.48487].

So [|\vec{L}| ≈ 0.485\ \text{kg·m}^2\text{/s}].

Practice 4. A planet (treated as a point mass) moves in an orbit. Its distance from the star changes from [r_1 = 2.0×10^{11} m] to [r_2 = 1.5×10^{11} m]. If its initial tangential speed at [r_1] is [v_1 = 3.00×10^{4} m/s], find its tangential speed [v_2] at [r_2] assuming no external torque (angular momentum conservation).

Solution:

For orbital motion (mass [m] cancels): [m r_1 v_1 = m r_2 v_2] ⇒ [r_1 v_1 = r_2 v_2].

Solve for [v_2]: [v_2 = (r_1 v_1) / r_2].

Substitute numbers: [v_2 = (2.0×10^{11} × 3.00×10^{4}) / 1.5×10^{11}].

Compute numerator: [2.0 × 3.00 = 6.00]; powers: [10^{11} × 10^{4} = 10^{15}]. So numerator = [6.00×10^{15}].

Divide: [6.00×10^{15} ÷ 1.5×10^{11}]. Compute mantissas: [6.00 ÷ 1.5 = 4.00]. Powers: [10^{15} ÷ 10^{11} = 10^{4}].

Thus [v_2 = 4.00 × 10^{4} = 4.00×10^{4} m/s].

So [v_2 = 40{,}000\ \text{m/s}].

Practice 5. A solid cylinder (mass [3.00 kg], radius [0.20 m]) rotates at [ω_1 = 5.00 rad/s]. It is gently placed on top of an identical identical solid cylinder initially at rest; after coupling they rotate together without slipping (they stick). Find the final angular speed [ω_f].

Solution:

Moment of inertia of one solid cylinder about its axis: [I = \tfrac{1}{2} M R^2].

Let [I] be the inertia of each; initial total angular momentum: [L_i = I ω_1] (the second cylinder has zero angular momentum).

Final inertia when both rotate together: [I_\text{total} = I + I = 2I].

Conservation of angular momentum: [I ω_1 = (2I) ω_f] ⇒ [ω_f = I ω_1 / (2I) = ω_1 / 2].

So [ω_f = 5.00 / 2 = 2.50 rad/s].

Practice 6 (optional). A rigid body has moment of inertia [I = 0.80 kg·m^2] and angular momentum [L = 1.60 kg·m^2/s]. Find its angular speed [ω] and rotational kinetic energy [K].

Solution:

Angular momentum relation: [L = I ω] ⇒ [ω = L / I].

[ω = 1.60 / 0.80 = 2.00 rad/s].

Rotational kinetic energy: [K = \tfrac{1}{2} I ω^2].

[K = 0.5 × 0.80 × (2.00)^2]. Compute: [(2.00)^2 = 4.00]; [0.5 × 0.80 = 0.40]; then [0.40 × 4.00 = 1.60].

So [K = 1.60 \ \text{J}].

11. Conceptual Questions

1. What physical quantity does angular momentum represent?

It represents the amount of rotational motion possessed by a body about a given axis.

2. How is angular momentum related to linear momentum?

It is the cross product of position vector and linear momentum: [ L = r × p ].

3. What does the direction of angular momentum indicate?

It indicates the axis about which rotation occurs and the sense of rotation, following the right-hand rule.

4. How is angular momentum affected by the choice of axis?

It changes because both [ r ] and [ I ] depend on the reference axis.

5. What happens to angular momentum if no external torque acts on a system?

It remains constant — this is the law of conservation of angular momentum.

6. Why does a figure skater spin faster when pulling arms inward?

Because pulling arms in reduces [ I ], and since [ L = I ω ] is conserved, [ ω ] increases.

7. Does angular momentum depend on the axis of rotation?

Yes, changing the axis changes the position vectors, and hence the angular momentum value.

8. Is angular momentum always conserved in all systems?

Only if the net external torque acting on the system is zero.

9. What is the relationship between torque and rate of change of angular momentum?

[ τ = dL/dt ]. Torque causes the angular momentum to change over time.

10. How can angular momentum be conserved if rotational speed changes?

Because [ I ] and [ ω ] can change inversely such that [ I ω = constant ].

11. How is angular momentum related to rotational kinetic energy?

[ K = L^2 / (2I) ]. This shows that energy depends on the square of angular momentum.

12. Can angular momentum be zero for a moving body?

Yes, if the position vector and linear momentum are parallel (their cross product is zero).

13. What is the difference between orbital and spin angular momentum?

Orbital angular momentum is due to motion around an external point; spin angular momentum is due to rotation about its own axis.

14. Does changing the moment of inertia always change angular momentum?

Not if there is no external torque — the product [ I ω ] remains constant.

15. Why is angular momentum important in astronomy?

It explains rotational behaviors of planets, stars, and galaxies, which conserve angular momentum as they form or collapse.

12. FAQ / Common Misconceptions

1. Is angular momentum always directed along the axis of rotation?

Only in cases of symmetric rotation about a fixed axis; in general, it may not align exactly with the angular velocity vector.

2. Does a constant angular velocity mean angular momentum is conserved?

Not necessarily — conservation of angular momentum requires zero external torque, not constant angular velocity.

3. If torque is zero, can angular velocity still change?

Yes, if the moment of inertia changes (as in a skater pulling arms in) while maintaining constant [ L ].

4. Is angular momentum only relevant for rotating rigid bodies?

No. It applies to any motion around a point, including particles in orbit (e.g., planets around the Sun).

5. Can angular momentum be negative?

Yes, its direction is determined by the right-hand rule. Opposite sense of rotation corresponds to negative angular momentum.