Physics and Mathematics

Stoke’s Law

1. Statement of the Law

Stokes’ Law gives the viscous drag force experienced by a small spherical body moving slowly through a viscous fluid.

When a small sphere moves through a viscous fluid with low velocity, the viscous drag force acting on it is directly proportional to the fluid’s viscosity, the velocity of the sphere, and its radius.

Mathematically,

[F = 6 \pi \eta r v]

Where:

- [F] = Viscous drag force

- [\eta] = Coefficient of viscosity of the fluid

- [r] = Radius of the sphere

- [v] = Velocity of the sphere

2. Explanation and Mathematical Derivation

When a sphere moves with velocity [v] through a viscous fluid, layers of the fluid stick to its surface and resist motion.

This resistance arises due to viscous shear stress.

For small Reynolds number (Re < 1), the flow is steady and laminar, and the viscous drag is given by Stokes as:

[F = 6 \pi \eta r v]

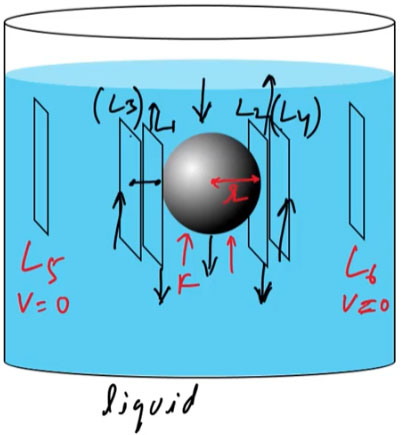

Equilibrium Condition (Terminal Velocity)

When the sphere falls freely under gravity in a fluid, three forces act on it:

- Weight (W) = [\dfrac{4}{3} \pi r^3 \rho g] (downward)

- Buoyant Force (B) = [\dfrac{4}{3} \pi r^3 \sigma g] (upward)

- Viscous Force (F) = [6 \pi \eta r v] (upward)

At terminal velocity [v_t], net force = 0:

[W = B + F]

Substituting,

[\dfrac{4}{3} \pi r^3 \rho g] [= \dfrac{4}{3} \pi r^3 \sigma g] [+ 6 \pi \eta r v_t]

Simplifying:

[v_t] [= \dfrac{2 r^2 g (\rho – \sigma)}{9 \eta}]

Where:

[\rho] = Density of sphere, [\sigma] = Density of fluid.

3. Dimensions and Units

| Quantity | Symbol | SI Unit | Dimensions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viscosity | [\eta] | Pa·s | [M L^{-1} T^{-1}] |

| Drag Force | [F] | N | [M L T^{-2}] |

| Velocity | [v] | m/s | [L T^{-1}] |

4. Key Features

- Valid for laminar flow and small spherical bodies.

- Applicable only when Reynolds number < 1.

- Drag force increases linearly with velocity.

- Explains terminal velocity of raindrops or pollen grains.

- Helps in determining viscosity of fluids experimentally.

- The force direction is opposite to motion of the body.

- The relation is independent of fluid density for drag alone.

- Basis for the falling sphere viscometer experiment.

5. Important Formulas to Remember

| Formula | Description |

|---|---|

| [F] [= 6 \pi \eta r v] | Stokes’ law (drag force) |

| [v_t] [= \dfrac{2 r^2 g (\rho – \sigma)}{9 \eta}] | Terminal velocity of a sphere |

| [Re] [= \dfrac{2 r \rho v}{\eta}] | Reynolds number (for laminar check) |

| [W = B + F] | Condition for terminal velocity |

6. Conceptual Questions with Solutions

1. Why does a falling sphere eventually move with constant velocity?

Because the viscous drag and buoyant force balance the weight at terminal velocity, making net force zero.

2. Why is Stokes’ law valid only for slow motion?

At high velocity, flow becomes turbulent, and the drag is no longer proportional to velocity.

3. What happens if the fluid is more viscous?

Greater viscosity causes higher drag, reducing terminal velocity.

4. Does Stokes’ law depend on the density of the fluid?

For drag force alone, no — it depends only on viscosity, not density.

5. Why does a large sphere fall faster in the same fluid?

Terminal velocity increases with the square of radius ([v_t ∝ r^2]).

6. What causes viscous force?

Internal friction between adjacent fluid layers moving with different velocities.

7. Why is the direction of viscous force opposite to motion?

Because it resists relative motion of the fluid layers.

8. What is the physical meaning of viscosity?

Viscosity is the property of a fluid that resists flow or deformation.

9. Why do small raindrops fall slowly?

Because their radius is small, reducing terminal velocity ([v_t ∝ r^2]).

10. What happens when Reynolds number exceeds 1?

Flow becomes nonlinear and Stokes’ law no longer holds.

11. Why does the drag increase when velocity increases?

Because viscous resistance increases proportionally with speed.

12. Can Stokes’ law be used for gases?

Yes, if the motion is slow and laminar; gases also exhibit viscosity.

13. How can viscosity of a fluid be measured using Stokes’ law?

By measuring the terminal velocity of a falling sphere and using [\eta = \dfrac{2 r^2 g (\rho – \sigma)}{9 v_t}].

14. Why does oil have greater viscosity than water?

Because molecular forces between oil molecules are stronger than in water.

15. Why do very small particles remain suspended in air?

For extremely small particles, viscous drag dominates over weight, preventing fast settling.

7. FAQ / Common Misconceptions

1. Is the viscous force always constant?

No, it depends on velocity; as speed increases, drag increases linearly.

2. Does Stokes’ law apply for non-spherical bodies?

No, it is derived strictly for **perfect spheres**.

3. Is drag force proportional to area?

No, it depends on radius and velocity linearly, not on area directly.

4. Why is terminal velocity smaller in denser fluids?

Because viscosity and buoyant force both increase in denser fluids, reducing velocity.

5. Is buoyant force neglected in Stokes’ law?

Yes, the basic Stokes’ expression accounts only for viscous drag, not buoyancy.

6. Why is flow steady near small spheres?

Because velocity is low and the fluid adjusts instantly to motion, ensuring laminar flow.

7. Is Stokes’ law an experimental or theoretical law?

It is derived theoretically from fluid dynamics under laminar flow assumptions.

8. Can terminal velocity be reached in vacuum?

No, viscosity (and thus drag) is absent in vacuum.

9. Why do larger raindrops break up while falling?

Because turbulence develops, and Stokes’ law no longer applies.

10. Does temperature affect viscous drag?

Yes, as viscosity decreases with temperature, the drag force decreases.

8. Practice Questions (with Step-by-Step Solutions)

Q1. A steel ball of radius [1 \times 10^{-3} \ m] falls through oil of viscosity [0.1 \ Pa·s]. Density of steel is [8000 \ kg/m^3] and that of oil is [900 \ kg/m^3]. Find terminal velocity.

Solution:

[v_t] [= \dfrac{2 r^2 g (\rho – \sigma)}{9 \eta}]

[= \dfrac{2 (10^{-3})^2 \times 9.8 (8000 – 900)}{9 \times 0.1}] [= 0.0157 \ m/s]

Q2. The terminal velocity of a small sphere in a viscous fluid is 2 cm/s. If its radius is doubled, find new velocity.

Solution:

[v_t ∝ r^2] [⇒ v’ = 4 v_t = 8 \ cm/s]

Q3. Find the viscosity of a liquid if a steel ball of radius [1 , mm] attains terminal velocity [0.02 \ m/s]. (Given [\rho – \sigma = 7000 \ kg/m^3]).

Solution:

[\eta] [= \dfrac{2 r^2 g (\rho – \sigma)}{9 v_t}]

[= \dfrac{2 (10^{-3})^2 \times 9.8 \times 7000}{9 \times 0.02}] [= 0.76 \ Pa·s]

Q4. Explain why oil drops in air reach terminal velocity faster than steel balls in oil.

Solution:

Because air’s viscosity is very low, the velocity required to balance weight is reached quickly, hence terminal velocity is achieved faster.

Q5. A raindrop of radius [1 \ mm] falls in air ([\eta = 1.8 \times 10^{-5} \ Pa·s], [\rho_{drop} = 1000 \ kg/m^3], [\rho_{air} = 1.2 \ kg/m^3]). Find terminal velocity.

Solution:

[v_t] [= \dfrac{2 (10^{-3})^2 \times 9.8 (1000 – 1.2)}{9 \times 1.8 \times 10^{-5}}] [= 12.1 \ m/s]