Physics and Mathematics

Acceleration Due to Gravity

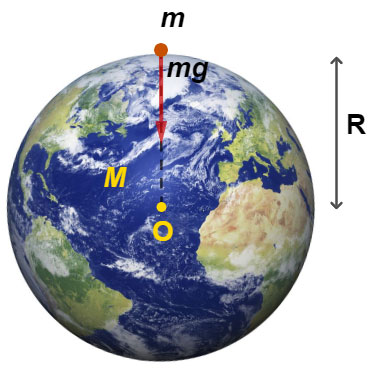

1. Concept Overview

When a body falls freely toward the Earth (or any planet), it experiences a uniform acceleration directed toward the planet’s center.

This acceleration is called the acceleration due to gravity, denoted by ( g ).

It arises due to the gravitational force exerted by the planet on the object.

Thus, acceleration due to gravity is a measure of the intensity of the gravitational field near the surface of the planet.

[

\boxed{g = G \dfrac{M}{R^2}}

]

where

- [ G ] = Universal gravitational constant

- [ M ] = Mass of the planet

- [ R ] = Radius of the planet

2. Explanation and Mathematical Derivation

Consider a planet of mass [ M ] and radius [ R ].

Let a body of mass [ m ] be placed near its surface.

By Newton’s law of gravitation, the force of attraction between the planet and the body is:

[F = G \dfrac{M m}{R^2}]

By Newton’s Second Law of Motion, the force on a body is also:

[F = m a = m g]

Equating both expressions:

[

m g = G \dfrac{M m}{R^2}

]

Cancelling [ m ] (since it is non-zero):

[

\boxed{g = G \dfrac{M}{R^2}}

]

Hence, the acceleration due to gravity depends only on the mass and radius of the planet, not on the body’s mass.

Derivation for Variation of ( g )

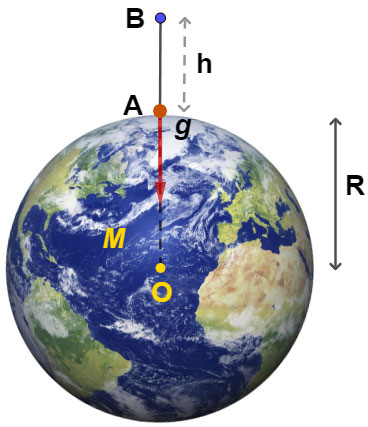

(a) Variation with Altitude

If an object is at a height [ h ] above the Earth’s surface, its distance from the center becomes [ R_E + h ].

[

g’ = G \dfrac{M_E}{(R_E + h)^2}

]

Dividing by [ g = G \dfrac{M_E}{R_E^2} ]:

[

\dfrac{g’}{g} = \left(\dfrac{R_E}{R_E + h}\right)^2

]

[

\boxed{g’ = g \left(\dfrac{R_E}{R_E + h}\right)^2}

]

For [ h \ll R_E ]:

[

g’ \approx g \left(1 – \dfrac{2h}{R_E}\right)

]

So, [ g ] decreases with height.

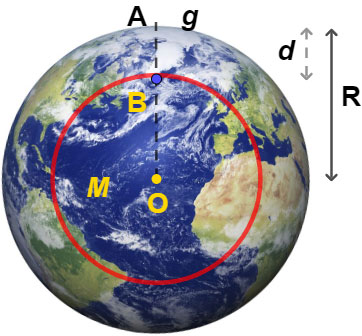

(b) Variation with Depth

At a depth [ d ] below the Earth’s surface:

Only the mass enclosed within radius [ (R_E – d) ] contributes to the gravitational force (by Newton’s Shell Theorem).

[

M’ = M_E \left(\dfrac{R_E – d}{R_E}\right)^3

]

[g’ = G \dfrac{M’}{(R_E – d)^2}] [= G \dfrac{M_E}{R_E^2} \left(1 – \dfrac{d}{R_E}\right)]

[

\boxed{g’ = g \left(1 – \dfrac{d}{R_E}\right)}

]

Thus, [ g ] decreases linearly with depth, becoming zero at the center.

(c) Variation with Latitude

Because Earth rotates about its axis, there is a centrifugal acceleration at latitude [ \lambda ]:

[

a_c = \omega^2 R_E \cos^2 \lambda

]

Hence, effective acceleration due to gravity:

[

g’ = g – \omega^2 R_E \cos^2 \lambda

]

At equator [( \lambda = 0° )]: [ g’ = g – \omega^2 R_E ]

At poles [( \lambda = 90° )]: [ g’ = g ]

Therefore, [ g ] is maximum at poles and minimum at equator.

3. Dimensions and Units

| Quantity | Symbol | SI Unit | Dimensions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acceleration due to Gravity | [ g ] | m/s² | ([L T^{-2}]) |

| Gravitational Constant | [ G ] | N·m²/kg² | ([M^{-1} L^3 T^{-2}]) |

| Angular Velocity of Earth | [ \omega ] | rad/s | ([T^{-1}]) |

| Mass of Earth | [ M_E ] | kg | ([M]) |

| Radius of Earth | [ R_E ] | m | ([L]) |

4. Key Features

- [ g = G \dfrac{M}{R^2} ] — depends only on planet’s mass and radius.

- [ g ] is independent of the mass or composition of the falling body.

- [ g ] is directed toward the center of the planet.

- [ g ] decreases with height and depth.

- [ g ] varies with latitude due to Earth’s rotation.

- [ g ] is maximum at poles and minimum at equator.

- [ g ] becomes zero at the Earth’s center.

- The effective gravity at any point includes both gravitational and centrifugal effects.

- The variation in [ g ] affects pendulum time period and weight measurement.

- The standard value at sea level and 45° latitude is 9.80665 m/s².

5. Important Formulas to Remember

| Concept | Formula | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Definition | [ g = G \dfrac{M}{R^2} ] | Surface gravity of planet |

| At Height [ h ] | [ g’ = g \left(\dfrac{R}{R + h}\right)^2 ] | Decreases with altitude |

| Approx. for [ h \ll R ] | [ g’ = g(1 – \dfrac{2h}{R}) ] | Linear decrease |

| At Depth [ d ] | [ g’ = g(1 – \dfrac{d}{R}) ] | Linear decrease |

| At Latitude [ \lambda ] | [ g’ = g – \omega^2 R \cos^2 \lambda ] | Due to rotation |

| Relation to Weight | [ W = mg ] | Gravitational pull on body |

| On Other Planets | [ g_P = G \frac{M_P}{R_P^2} ] | Depends on planet’s mass and radius |

6. Conceptual Questions with Solutions

1. What causes acceleration due to gravity?

It is caused by the gravitational attraction of the planet’s mass on a body.

2. Why is \( g \) independent of the mass of the falling body?

Because in \( F = ma = G \frac{M m}{R^2} \), the mass \( m \) cancels out.

3. What is the direction of \( g \)?

It is always directed toward the center of the Earth.

4. Why is \( g \) not constant on Earth?

Due to variation in altitude, depth, latitude, and local density.

5. What is the value of \( g \) at the poles and equator?

Maximum at poles, minimum at equator.

6. What happens to \( g \) as we go above the Earth’s surface?

It decreases as \( g’ = g \left(\frac{R}{R + h}\right)^2 \).

7. What happens to \( g \) as we go deeper inside Earth?

It decreases linearly and becomes zero at the center.

8. What is the cause of variation of \( g \) with latitude?

The Earth’s rotation causes a centrifugal force opposing gravity.

9. What is the acceleration due to gravity on the Moon?

\( g_M = 1.62 \, \text{m/s}^2 \).

10. How does \( g \) affect the period of a simple pendulum?

\( T = 2\pi \sqrt{\frac{L}{g}} \), so as \( g \) decreases, \( T \) increases.

11. What will be \( g \) if the Earth stops rotating?

\( g’ = g \), because there will be no centrifugal reduction.

12. Does \( g \) depend on shape or density of the body?

No, it depends only on planet’s properties.

13. Is \( g \) same everywhere on Moon?

No, it also varies slightly with lunar latitude and altitude.

14. What is the value of \( g \) at the center of Earth?

Zero, since gravitational forces cancel in all directions.

15. Why do astronauts feel weightless though \( g \) acts on them?

They are in free fall with respect to Earth; apparent weight = 0.

7. FAQ / Common Misconceptions

1. \( g \) is same everywhere on Earth.

**False.** It varies with altitude, depth, and latitude.

2. \( g \) depends on the mass of the falling object.

**False.** It is independent of the object’s mass.

3. \( g \) and \( G \) are the same.

**False.** \( G \) is universal constant; \( g \) is local gravitational acceleration.

4. \( g \) is always 9.8 m/s².

**False.** That is the average value; it varies slightly.

5. \( g \) increases with height.

**False.** It decreases with altitude.

6. At the center of Earth, \( g \) is infinite.

**False.** It is zero.

7. Centrifugal force increases \( g \).

**False.** It decreases the effective value of \( g \).

8. The equator has higher \( g \) because it is larger.

**False.** It has lower \( g \) due to faster rotation.

9. Acceleration due to gravity is the same on all planets.

**False.** It varies with each planet’s mass and radius.

10. Weightlessness means absence of gravity.

**False.** It means absence of apparent weight, not gravity.

8. Practice Questions (Step-by-Step Solutions)

Q1. Find the value of [ g ] on a planet whose mass and radius are half those of Earth.

Solution:

[

g’ = G \dfrac{(M_E/2)}{(R_E/2)^2} = 2g

]

Hence, [ g’ = 2g = 19.6 \text{m/s}^2 ].

Q2. Calculate [ g’ ] at a height of 400 km above Earth.

[

h = 4 \times 10^5 \text{m} , R = 6.4 \times 10^6 \text{m}

]

[

g’ = 9.8 \left(\dfrac{6.4}{6.8}\right)^2 = 8.5 \text{m/s}^2

]

Q3. Find [ g’ ] at a depth of 1600 km below Earth’s surface.

[

g’ = g \left(1 – \dfrac{d}{R}\right)] [= 9.8 \left(1 – \dfrac{1600}{6400}\right)] [= 7.35 \text{m/s}^2

]

Q4. What is the effective value of ( g ) at the equator due to rotation of Earth?

[\omega = 7.27 \times 10^{-5} \text{rad/s} , R = 6.4 \times 10^6]

[g’ = g – \omega^2 R] [= 9.8 – (7.27 \times 10^{-5})^2 \times 6.4 \times 10^6] [= 9.77 \text{m/s}^2]

Q5. Calculate [ g ] on Mars where [ M = 6.42 \times 10^{23} \text{kg}, R = 3.39 \times 10^6 \text{m} ].

[g = 6.67 \times 10^{-11} \times \dfrac{6.42 \times 10^{23}}{(3.39 \times 10^6)^2}] [= 3.71 \text{m/s}^2]

Therefore, acceleration due to gravity is the local intensity of the planet’s gravitational field — varying slightly with position but fundamental to all motion near its surface.