Physics and Mathematics

Boyle’s Law

1. Statement of the Law

At constant temperature, the pressure of a given mass of gas is inversely proportional to its volume.

[\text{If temperature (T) is constant}] [\text{then }] [p \propto \dfrac{1}{V}]

or

[pV = \text{constant}]

This relationship is known as Boyle’s Law, discovered by Robert Boyle in 1662.

2. Explanation and Mathematical Derivation

Let:

- [p₁, V₁] = initial pressure and volume

- [p₂, V₂] = final pressure and volume

According to Boyle’s Law:

[p₁V₁ = p₂V₂] [= \text{constant}]

Hence,

[\dfrac{p₁}{p₂}] [= \dfrac{V₂}{V₁}]

This means that when pressure increases, volume decreases, and vice versa, provided temperature remains constant.

Graphical Representation

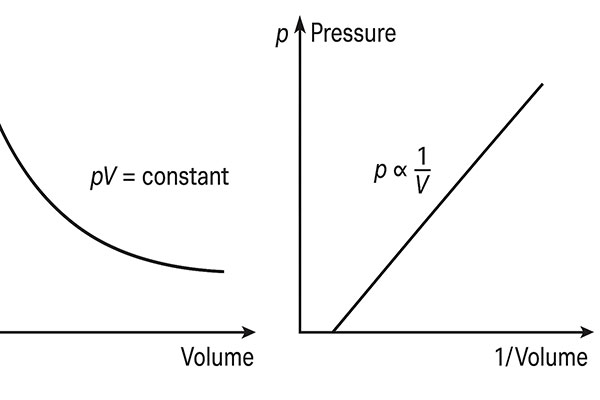

- p–V Curve (Isothermal Curve)

If we plot a graph between pressure (p) and volume (V), we obtain a rectangular hyperbola since [pV = constant].

- p–1/V Curve

A straight line passing through the origin is obtained if pressure (p) is plotted against 1/V.

These curves are called isothermal curves because the temperature is constant during the process.

3. Dimensions and Units

| Quantity | Symbol | Unit | Dimensions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pressure | [p] | N·m⁻² or Pa | [M¹L⁻¹T⁻²] |

| Volume | [V] | m³ | [L³] |

| Product [pV] | — | J (work or energy) | [M¹L²T⁻²] |

4. Key Features

- Valid only if temperature remains constant.

- The product pV for a given mass of gas is constant.

- The graph p vs V is a rectangular hyperbola.

- The graph p vs 1/V is a straight line through the origin.

- Applicable to ideal gases and approximately to real gases at low pressure.

- Explains the compressibility and expansion of gases.

5. Important Formulas to Remember

| Formula | Description |

|---|---|

| [p \propto \dfrac{1}{V}] | Basic form of Boyle’s Law |

| [pV = \text{constant}] | Mathematical expression |

| [p₁V₁ = p₂V₂] | Relation between two states |

| [\dfrac{p₁}{p₂}] [= \dfrac{V₂}{V₁}] | Alternate form |

| [pV = nRT] | General ideal gas equation (constant T ⇒ Boyle’s Law) |

6. Conceptual Questions with Solutions

1. What remains constant in Boyle’s Law?

Temperature remains constant in Boyle’s Law. The process is therefore **isothermal**.

2. What happens to the volume if pressure is doubled?

From [p₁V₁ = p₂V₂], if [p₂ = 2p₁], then [V₂ = \dfrac{V₁}{2}]. Volume becomes half.

3. What is the nature of the p–V graph?

It is a rectangular hyperbola because [pV = constant].

4. Why is temperature kept constant in Boyle’s Law?

Because Boyle’s Law deals with only pressure and volume; any temperature change would affect the internal energy.

5. What happens to the pressure if volume is halved?

From [p₁V₁ = p₂V₂], if [V₂ = V₁/2], then [p₂ = 2p₁]. Pressure doubles.

6. Can Boyle’s Law be applied to solids and liquids?

No, because solids and liquids are nearly incompressible.

7. What is meant by an isothermal process?

A process during which temperature remains constant.

8. What happens to the kinetic energy of gas molecules in Boyle’s Law?

It remains constant since temperature (and hence average kinetic energy) is constant.

9. What is the SI unit of the Boyle’s constant (pV)?

Joule (J).

10. Can Boyle’s Law be derived from the ideal gas equation?

Yes. From [pV = nRT], if T and n are constant, then [pV = constant].

11. What type of curve do we get for p vs 1/V?

A straight line passing through the origin.

12. Why does the graph of p vs V never touch the axes?

Because neither pressure nor volume can become zero.

13. What is the physical significance of pV = constant?

It indicates that the product of pressure and volume remains the same for a fixed temperature.

14. Is Boyle’s Law valid for high pressures?

No, because gases deviate from ideal behavior at high pressure.

15. What is the relation between Boyle’s Law and Charles’s Law?

Both are special cases of the **ideal gas law** [pV = nRT].

7. FAQ / Common Misconceptions

1. Boyle’s Law applies only to ideal gases.

True in strict sense, but approximately valid for real gases at low pressure and high temperature.

2. Temperature must not change during the process.

Correct — any temperature variation invalidates Boyle’s Law.

3. The law implies constant energy.

Not necessarily — only average kinetic energy is constant, not total energy.

4. Volume becomes zero at infinite pressure.

Incorrect — gases cannot be compressed infinitely; they liquefy at high pressure.

5. The p–V graph is a straight line.

No, it’s a hyperbola.

6. Boyle’s Law can be used for rapid compression.

Not always — rapid compression may cause heating, violating isothermal condition.

7. p and V are directly proportional.

No, they are inversely proportional.

8. Boyle’s Law cannot explain gas compressibility.

It actually does — showing inverse relationship between p and V.

9. pV = constant means p and V are individually constant.

No, their **product** is constant, not each separately.

10. Boyle’s Law violates the ideal gas equation.

It is a special case of the ideal gas equation for constant temperature.

8. Practice Questions (with Step-by-Step Solutions)

Q1. A gas occupies 600 cm³ at a pressure of 100 kPa. What is its volume at 150 kPa, temperature constant?

Solution:

[p₁V₁ = p₂V₂]

[\Rightarrow 100 × 600] [= 150 × V₂]

[V₂ = 400 cm³.]

Q2. At constant temperature, a gas of volume 2 L is at 2 atm. What will be the pressure if volume is increased to 3 L?

Solution:

[p₁V₁ = p₂V₂]

[2 × 2 = p₂ × 3]

[p₂ = 1.33 atm.]

Q3. The pressure of a gas is reduced by half. What happens to its volume?

Solution:

Since [p₁V₁ = p₂V₂] and [p₂ = p₁/2],

[V₂ = 2V₁.] Volume doubles.

Q4. A gas has 2 L volume at 760 mm Hg. Find its pressure when volume is 3 L.

Solution:

[p₁V₁ = p₂V₂]

[760 × 2 = p₂ × 3]

[p₂ = 506.7 mm Hg.]

Q5. A sample of gas has pressure 3 × 10⁵ Pa and volume 4 × 10⁻³ m³. Find the work done if volume expands to 8 × 10⁻³ m³ isothermally.

Solution:

Work done in isothermal process:

[W = p₁V₁] [\ln \dfrac{V₂}{V₁}]

[= 3 × 10⁵ × 4 × 10⁻³ \ln 2] [= 831 J.]