Physics and Mathematics

Eddy Current

1. Concept Overview / Statement of the Concept

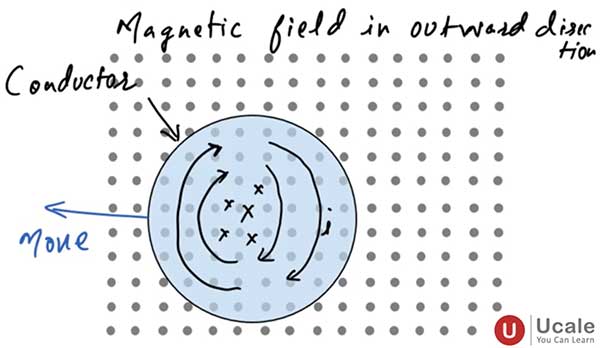

Eddy currents are circular loops of electric current induced within conductors when they experience a changing magnetic flux.

Unlike induced currents in wires (which follow a fixed path), eddy currents flow in closed swirling patterns inside the bulk of a metal.

They arise because:

- According to Faraday’s Law, a changing magnetic field induces emf.

- In a conductor, this induced emf appears in multiple directions simultaneously.

- This produces circulating loops of current, similar to eddies formed in flowing water — hence the name eddy currents.

These currents obey Lenz’s Law, so they flow in such a direction that their magnetic fields oppose the change in magnetic flux that produced them.

Eddy currents are generally undesirable inside electrical machines (because they cause heating and energy loss), but they are also used in many useful applications like induction cooktops, speedometers, magnetic braking, metal detectors, etc.

2. Clear Explanation & Mathematical Derivation

How Eddy Currents Form?

Consider a solid metal block placed in a magnetic field that is changing with time.

According to Faraday’s Law:

[\mathcal{E} = – \dfrac{d\Phi_B}{dt}]

But the conductor has no fixed path for current to flow.

So, emf appears around many tiny closed loops inside the conductor.

Each loop experiences a small emf:

[d\mathcal{E} = -\dfrac{d\Phi}{dt}]

This creates a current in that loop:

[dI = \dfrac{d\mathcal{E}}{R_{\text{loop}}}]

Thus, currents swirl in the conductor, forming eddy current loops.

Heat Loss Due to Eddy Currents

Eddy currents cause heating due to Joule’s law:

[P = I^2 R]

If the conductor is thick and continuous, resistance is low, so large eddy currents form, causing significant energy loss.

Reduction of Eddy Currents

In transformers and electrical machines, eddy currents are undesirable.

To reduce them:

- The core is made of thin laminated sheets.

- Sheets are insulated from each other.

- Effective area for current loops becomes very small → resistance increases → eddy currents reduce.

Reduction factor:

[I \propto \dfrac{1}{R}]

Lamination increases resistance → reduces eddy currents.

3. Dimensions and Units

- Eddy current itself is electric current, so its SI unit is ampere (A).

- Generated emf follows Faraday’s Law → unit is volt (V).

- Eddy current power loss:

[P = I^2 R] → unit is watt (W).

4. Key Features

- Produced by changing magnetic field.

- Induced in solid conductors, not only wires.

- Form closed circular loops (like water eddies).

- Follow Lenz’s Law (oppose flux change).

- Cause heating, known as eddy current loss.

- Can be reduced by lamination or increasing resistance.

- Used in magnetic braking, induction furnaces, metal detectors, speedometers, etc.

5. Important Formulas to Remember

| Concept | Formula |

|---|---|

| Induced emf | [\mathcal{E} = -\dfrac{d\Phi}{dt}] |

| Eddy current heating | [P = I^2 R] |

| Magnetic braking force (qualitative) | [F \propto I B] |

| Eddy current magnitude approx. | [I \propto \dfrac{d\Phi/dt}{R}] |

6. Conceptual Questions with Solutions

1. Why do eddy currents form inside solid metals?

Because a changing magnetic field induces emf in many tiny loops inside the metal, and each loop produces circular current flow according to Faraday’s Law.

2. Why do eddy currents always oppose the cause producing them?

They follow Lenz’s Law: the magnetic field created by eddy currents opposes the change in original magnetic flux.

3. Why are eddy currents stronger in thick metal sheets?

Because resistance is low in thick sheets, allowing larger current loops.

4. Why does lamination reduce eddy current loss?

It breaks the conductor into thin insulated slices, increasing resistance and restricting large current loops.

5. Why does a magnet fall slowly through a copper tube?

Falling magnet changes flux in the tube → induces eddy currents → they oppose motion → slowing the fall.

6. Why is copper used in magnetic braking systems?

Copper is highly conductive → produces strong eddy currents → strong opposing magnetic field → effective braking.

7. Why do induction cooktops heat vessels without heating the cooktop itself?

Eddy currents are induced in the vessel (ferromagnetic), not in the cooktop surface → heat generated only in vessel.

8. Why do energy meters use eddy currents?

Eddy currents produce torque proportional to power consumption, enabling accurate measurement.

9. Why are eddy currents considered a loss in transformers?

They generate heat in the iron core, wasting electrical energy.

10. Why does relative motion between conductor and magnetic field matter?

Because emf is induced only when magnetic flux linked with conductor changes.

11. Why can eddy currents be harmful in electrical machines?

They cause heating → reduce efficiency → damage insulation.

12. Why are eddy currents desirable in metal detectors?

The presence of metal alters eddy current patterns → changes detected by circuitry.

13. Why does increasing resistivity reduce eddy currents?

Because current magnitude is inversely proportional to resistance: [I \propto \dfrac{1}{R}].

14. Why does an induction furnace heat metal very quickly?

Strong alternating magnetic field induces large eddy currents in the metal → intense heating.

15. Why do rotating metal discs experience drag in magnetic fields? Because changing flux induces eddy currents which oppose rotation, producing a braking torque.

7. FAQ / Common Misconceptions

1. Do eddy currents flow only on the surface of metals?

No. They flow throughout the bulk, forming circular loops inside the conductor.

2. Are eddy currents always harmful?

No. They are harmful in transformers but useful in brakes, induction furnaces, and speedometers.

3. Do eddy currents require a closed external circuit?

No. They form closed loops within the conductor itself.

4. Does a steady magnetic field produce eddy currents?

No. Only a **changing** magnetic field produces them.

5. Is motion necessary for eddy currents?

Not always. Even without motion, a changing magnetic field induces them.

6. Is lamination used to increase eddy currents?

No. It is used to reduce them by increasing resistance.

7. Are eddy currents present in non-metals?

No. They require free electrons, so they occur in good conductors.

8. Do eddy currents always oppose motion?

They oppose **change in flux**, not motion itself. Opposing motion occurs only when motion changes flux.

9. Are eddy currents the same as surface currents?

No. Eddy currents circulate inside the material, not on the surface.

10. Is magnetic braking caused by friction?

No. It is caused by electromagnetic induction, not mechanical friction.

8. Practice Questions (with Step-by-Step Solutions)

Practice Q1 — Motional emf in a rod

A conducting rod of length [0.20\ \text{m}] moves perpendicular to a magnetic field of [0.40\ \text{T}] with speed [3.0\ \text{m/s}].

Find the motional emf induced across the ends of the rod.

Solution

- Formula for motional emf:

[\mathcal{E} = B l v] - Substitute:

[\mathcal{E} = 0.40 \times 0.20 \times 3.0] - Multiply carefully:

[0.40 \times 0.20 = 0.080]

[0.080 \times 3.0 = 0.240] - Answer:

[\mathcal{E} = 0.240\ \text{V}]

Practice Q2 — Current and power from induced emf

The rod in Q1 is part of a closed circuit whose total resistance is [2.0\ \Omega]. Find (a) the induced current and (b) the power dissipated as heat.

Solution

(a) Induced current using Ohm’s law:

- [I = \dfrac{\mathcal{E}}{R}]

- From Q1, [\mathcal{E} = 0.240\ \text{V}], [R = 2.0\ \Omega]

- [I = \dfrac{0.240}{2.0} = 0.120\ \text{A}]

(b) Power dissipated (Joule heating):

- [P = I^2 R]

- [I^2 = (0.120)^2 = 0.0144]

- [P = 0.0144 \times 2.0] [= 0.0288\ \text{W}]

Answer: (a) [0.120\ \text{A}] (b) [0.0288\ \text{W}]

Practice Q3 — Average induced emf and energy dissipated

A square conducting loop of side [0.10\ \text{m}] (area [0.01\ \text{m}^2]) is pulled out of a uniform magnetic field [B = 0.50\ \text{T}]. The flux through the loop falls uniformly from initial value to zero in [0.20\ \text{s}]. Loop resistance is [0.50\ \Omega]. Find (a) the average induced emf, (b) the average induced current, and (c) the electrical energy dissipated during the 0.20 s.

Solution

- Initial flux: [\Phi_i = B A] [= 0.50 \times 0.01] [= 0.0050\ \text{Wb}]

Final flux: [\Phi_f = 0] - Change of flux: [\Delta\Phi = \Phi_f – \Phi_i] [= -0.0050\ \text{Wb}]

(Magnitude of change = 0.0050 Wb) - (a) Average induced emf:

[\mathcal{E}{\text{avg}}] [= -\dfrac{\Delta\Phi}{\Delta t}]

Take magnitude for size:

[|\mathcal{E}{\text{avg}}|] [= \dfrac{0.0050}{0.20}] [= 0.0250\ \text{V}] - (b) Average induced current:

[I_{\text{avg}}] [= \dfrac{|\mathcal{E}_{\text{avg}}|}{R}] [= \dfrac{0.0250}{0.50} = 0.0500\ \text{A}] - (c) Energy dissipated as heat = power × time = [I^2 R \Delta t]

[I^2 = (0.0500)^2] [= 0.00250]

[P = I^2 R] [= 0.00250 \times 0.50] [= 0.00125\ \text{W}]

Energy: [E = P \Delta t] [= 0.00125 \times 0.20] [= 0.000250\ \text{J}]

Answers: (a) [0.0250\ \text{V}], (b) [0.0500\ \text{A}], (c) [2.50\times10^{-4}\ \text{J}]

Practice Q4 — Effect of lamination on eddy losses

A solid metal plate exposed to an AC magnetic field suffers eddy-current losses of [5.0\ \text{W}]. Approximating the eddy currents’ equivalent resistance as [0.20\ \Omega], the induced emf amplitude corresponds to the observed loss. If the core is laminated so that the effective resistance of eddy loops increases by a factor of 10, estimate the new eddy-power loss (assume induced emf amplitude remains the same).

Solution

- Power for a given induced emf [\mathcal{E}] and loop resistance [R] is:

[P] [= \dfrac{\mathcal{E}^2}{R}] - If [R_{\text{old}}] [= 0.20\ \Omega] gives [P_{\text{old}}] [= 5.0\ \text{W}], then [\mathcal{E}^2] [= P_{\text{old}} R_{\text{old}}] [= 5.0 \times 0.20] [= 1.0]So [\mathcal{E}^2 = 1.0\ (\text{V}^2)] (this is the convenient intermediate value)

- New resistance: [R_{\text{new}}] [= 10 \times 0.20] [= 2.0\ \Omega]

- New power:

[P_{\text{new}}] [= \dfrac{\mathcal{E}^2}{R_{\text{new}}}] [= \dfrac{1.0}{2.0}] [= 0.50\ \text{W}]

Answer: New eddy loss ≈ [0.50\ \text{W}] (i.e., reduced by factor 10)

Practice Q5 — Simple magnetic braking proportionality

In a demonstration, a conducting plate moving at [4.0\ \text{m/s}] through a magnetic field experiences a braking force of [2.0\ \text{N}] due to eddy currents. For small speeds the braking force is approximately proportional to speed ([F \propto v]). Estimate the braking force when the plate moves at [6.0\ \text{m/s}].

Solution

- Proportionality: [\dfrac{F_2}{F_1}] [= \dfrac{v_2}{v_1}]

- Given [F_1 = 2.0\ \text{N}] at [v_1 = 4.0\ \text{m/s}], find [F_2] at [v_2 = 6.0\ \text{m/s}]:[F_2 = F_1 \dfrac{v_2}{v_1}] [= 2.0 \times \dfrac{6.0}{4.0}]

- Compute: [\dfrac{6.0}{4.0} = 1.5] → [F_2 = 2.0 \times 1.5] [= 3.0\ \text{N}]

Answer: Braking force ≈ [3.0\ \text{N}]