Physics and Mathematics

Electric Field Intensity Due to a Line Charge

1. Concept Overview

A line charge is a long, thin wire or rod on which charge is uniformly distributed.

If a charge [\lambda] (lambda) is present per unit length, it produces an electric field in the surrounding space.

To calculate this field, we use Gauss’s Law, because the system has cylindrical symmetry.

Understanding

- A long charged wire spreads electric field lines radially outward (for +λ) or inward (for –λ).

- The field is the same at all points at the same distance from the wire.

- This symmetry allows us to use a cylindrical Gaussian surface.

Gauss’s Law states:

[\oint \vec{E} \cdot d\vec{A}] [= \dfrac{Q_{\text{enclosed}}}{\varepsilon_0}]

We choose a cylindrical surface because:

- Field is radial

- Field is constant for a fixed radius

- Field is perpendicular to curved surface → simplifies calculation

2. Explanation and Mathematical Derivation

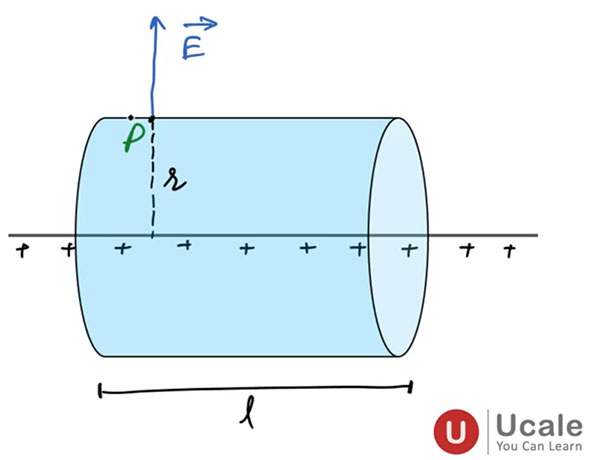

Consider a long straight wire carrying uniform line charge density [\lambda (C/m)].

Let us find the electric field at a distance [r] from the wire.

Gaussian Surface

We choose a cylinder of:

- Radius = [r]

- Length = [L]

Electric flux through the surface

The flux is only through the curved surface, not through flat ends.

Because the field is radial and perpendicular to curved surface:

[\oint \vec{E} \cdot d\vec{A}] [= E(2\pi rL)]

Charge enclosed

[Q_{\text{enclosed}}] [= \lambda L]

Apply Gauss’s Law

[E(2\pi rL)] [= \dfrac{\lambda L}{\varepsilon_0}]

Cancel [L]:

[E] [= \dfrac{\lambda}{2\pi \varepsilon_0 r}]

Thus, the electric field at distance [r] from an infinitely long line charge is:

[\boxed{E = \dfrac{\lambda}{2\pi \varepsilon_0 r}}]

Direction:

- Radially outward for [\lambda > 0]

- Radially inward for [\lambda < 0]

3. Dimensions and Units

Line charge density

[\lambda] = C/m

Electric field

[E] = [N/C] [= \dfrac{V}{m}]

Dimensions

[E] = [MLT^{-3}A^{-1}]

4. Key Features

- Field is inversely proportional to distance: [E \propto \dfrac{1}{r}]

- Useful for long straight wires (ideally infinite)

- Electric field is radial

- Field does not depend on the length of Gaussian surface (L cancels)

- Works only for uniform charge distribution

- Very important for:

- Charged rods

- Transmission lines

- Plasma physics

- Coaxial cable field calculations

5. Important Formulas to Remember

| S.No. | Formula | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | [E] [= \dfrac{\lambda}{2\pi\varepsilon_0 r}] | Field due to infinite line charge |

| 2 | [\lambda] [= \dfrac{Q}{L}] | Line charge density |

| 3 | [Q_{\text{enc}}] [= \lambda L] | Charge enclosed by Gaussian surface |

| 4 | [\phi = EA] | Electric flux |

| 5 | [A = 2\pi rL] | Curved surface area of Gaussian cylinder |

6. Conceptual Questions with Solutions

1. Why do we choose a cylindrical Gaussian surface?

Because the line charge produces a radially symmetric field, and a cylinder matches this symmetry, making [\vec{E}] constant on its curved surface.

2. Why is there no flux through the flat circular ends?

The field is radial, and flat ends are perpendicular to the axis → [\vec{E}] is **parallel** to the surface → flux = 0.

3. Why does the length of the cylinder (L) cancel out?

Because both flux and enclosed charge are proportional to [L], so they cancel in Gauss’s Law.

4. Why can we treat the wire as infinitely long?

For long wires, the field near the middle is nearly the same as for an infinite wire. Edge effects become negligible.

5. What happens if the wire is finite?

The field will no longer be exactly radial or uniform on the surface; Gauss’s Law becomes harder to apply.

6. Why does the electric field decrease as 1/r?

Because field lines spread out uniformly around the wire, forming expanding cylindrical shells.

7. Why can’t we use a spherical Gaussian surface?

Because the field is **not constant** on a sphere for a line charge.

8. Is the electric field inside a hollow charged tube zero?

Yes, if the tube is infinitely long and uniformly charged (similar reasoning as symmetry of shell).

9. If λ is negative, does E become negative?

No. Magnitude is positive, but **direction reverses** (inward).

10. Does E depend on the material of the wire?

No. Only on charge distribution.

11. Is the electric field uniform everywhere?

No. It varies with distance [r].

12. What happens to E as r → 0?

It becomes very large theoretically, but real wires have finite thickness.

13. Why is λ used instead of total charge?

Because the distribution is continuous and extends over a long length.

14. Can this formula be used near the ends of wire?

No. End effects make the field asymmetric.

15. Does medium affect field?

Yes. Replace [\varepsilon_0] with [\varepsilon].

7. FAQ / Common Misconceptions

1. “A line charge produces spherical field lines.”

False. It produces **cylindrical** symmetry.

2. “Flux must pass through flat circular ends.”

No. Because the field is parallel, not perpendicular.

3. “Field becomes zero at large distances.”

It decreases but never becomes exactly zero.

4. “Long wire must be infinitely long physically.”

No. Only needs to be long enough so that edge effects are negligible.

5. “λ is the charge per unit area.”

No. It is **charge per unit length**.

6. “Inside the wire, field is always zero.”

Not always; zero inside a conducting pipe, not necessarily inside a solid charged rod.

7. “Electric field direction depends on length of cylinder.”

No. Direction is purely radial.

8. “Gauss’s Law only works for line charges.”

It works for any closed surface; symmetry decides usefulness.

9. “A line charge produces the same field as a point charge.”

No. Point charge → [E \propto \dfrac{1}{r^2}], line charge → [E \propto \dfrac{1}{r}].

10. “Field is uniform everywhere.”

No, it depends on distance [r].

8. Practice Questions (With Step-by-Step Solutions)

Q1. A line charge has density [\lambda = 4 \mu C/m]. Find the electric field at 2 m from the wire.

Step 1: Use formula:

[E] [= \dfrac{\lambda}{2\pi\varepsilon_0 r}]

Step 2: Substitute:

[E] [= \dfrac{4 \times 10^{-6}}{2\pi (8.85 \times 10^{-12}) (2)}]

Step 3: Simplify:

[

E = 3.59 \times 10^{4} N/C

]

Q2. The electric field at a distance of 5 m from a long line charge is [1000 N/C]. Find λ.

[E] [= \dfrac{\lambda}{2\pi\varepsilon_0 r}]

[\lambda] [= E (2\pi\varepsilon_0 r)]

[\lambda] [= 1000 \cdot 2\pi \cdot 8.85 \times 10^{-12} \cdot 5]

[\lambda] [= 2.78 \times 10^{-7},C/m]

Q3. Field at 0.5 m from a line charge is twice the field at 1 m. Verify law.

[E] [= \dfrac{\lambda}{2\pi\varepsilon_0 r}]

At 0.5 m:

[E_1] [= \dfrac{\lambda}{2\pi\varepsilon_0 (0.5)}] [= 2 \dfrac{\lambda}{2\pi\varepsilon_0}]

At 1 m:

[E_2] [= \dfrac{\lambda}{2\pi\varepsilon_0 (1)}] [= \dfrac{\lambda}{2\pi\varepsilon_0}]

[

E_1 = 2E_2

]

Verified.

Q4. A line charge of length 3 m has total charge 12 μC. Find field at 2 m from its midpoint (assume long).

[\lambda] [= \dfrac{12 \times 10^{-6}}{3}] [= 4 \times 10^{-6} C/m]

Use:

[E] [= \dfrac{\lambda}{2\pi\varepsilon_0 r}]

[E] [= \dfrac{4 \times 10^{-6}}{2\pi(8.85 \times 10^{-12})(2)}]

[

E = 3.59 \times 10^4,N/C

]

Q5. Field at r is E. What is field at 2r?

[

E \propto \dfrac{1}{r}

]

[

E_{2r} = \dfrac{E}{2}

]