Physics and Mathematics

Field Intensity on Equatorial Line of a Dipole

1. Statement of the Law / Concept Overview

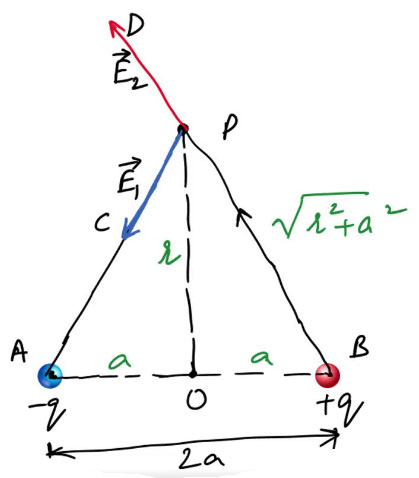

The electric field intensity on the equatorial line of a dipole is the net electric field at any point lying on the perpendicular bisector of the dipole.

On this line, the fields due to +q and −q act in opposite directions, leading to partial cancellation.

Thus, the equatorial field is always opposite in direction to the dipole moment and decreases with distance as [\dfrac{1}{r^3}] (far field).

2. Clear Explanation and Mathematical Derivation

Consider a dipole with:

- Charges: [+q] and [-q]

- Separation: [2a]

- Dipole moment: [\vec{p} = q(2a)\hat{l}]

Let point P lie on the equatorial line, at a distance [r] from the center.

Distances

The point P is equidistant from both charges:

[r_+ = r_-] [= \sqrt{a^2 + r^2}]

Electric Field Due to Each Charge

Electric field magnitude (same for both charges):

[E] [= \dfrac{1}{4\pi\varepsilon_0}\dfrac{q}{a^2 + r^2}]

Each field is not collinear with the dipole moment. We break it into components:

- Horizontal components cancel.

- Vertical components add.

Vertical component:

[E_{\text{component}}] [= E\cos\theta]

Where:

[\cos\theta] [= \dfrac{a}{\sqrt{a^2+r^2}}]

Net Electric Field on Equatorial Line

[E_{\text{equatorial}}] [= 2E\cos\theta]

Substitute values:

[

E_{\text{equatorial}}

= 2 \cdot \dfrac{1}{4\pi\varepsilon_0}\dfrac{q}{a^2+r^2}

\cdot\dfrac{a}{\sqrt{a^2+r^2}}

]

[

E_{\text{equatorial}}

= \dfrac{1}{4\pi\varepsilon_0}

\cdot\dfrac{2qa}{(a^2+r^2)^{3/2}}

]

Using dipole moment [p = 2aq]:

[

E_{\text{equatorial}}

= \dfrac{1}{4\pi\varepsilon_0}

\cdot\dfrac{p}{(a^2+r^2)^{3/2}}

]

Direction

The field is opposite to dipole moment (\vec{p}).

Far Field Approximation (when [r >> a])

[E_{\text{equatorial}}] [\approx \dfrac{1}{4\pi\varepsilon_0}\cdot\dfrac{p}{r^3}]

Direction: opposite to [\vec{p}].

3. Dimensions and Units

| Quantity | Dimensions | SI Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Electric Field | ([MLT^{-3}A^{-1}]) | N/C or V/m |

| Dipole Moment | ([ITA]) | C·m |

4. Key Features

- Magnitude is half of axial field at far distances:

[E_{\text{axial}}] [= 2E_{\text{equatorial}}] - Field direction is opposite to dipole moment.

- Field decreases as [\dfrac{1}{r^3}].

- Horizontal components cancel; vertical components add.

- Works for any dipole in free space.

- Field is non-uniform.

5. Important Formulas to Remember

| Formula | Meaning |

|---|---|

| [p = 2aq] | Dipole moment |

| [E_{\text{equatorial}}] [= \dfrac{1}{4\pi\varepsilon_0}\cdot\dfrac{p}{(a^2+r^2)^{3/2}}] | Exact field |

| [E_{\text{equatorial}}] [\approx \dfrac{1}{4\pi\varepsilon_0}\cdot\dfrac{p}{r^3}] | Far field |

| Direction = Opposite to (\vec{p}) | Always true |

6. Conceptual Questions with Solutions (15)

1. Why do horizontal components cancel on the equatorial line?

Because the point is symmetrically located; each charge contributes equal horizontal components in opposite directions.

2. Why is the equatorial field opposite to dipole moment?

At the equatorial line, the field of –q dominates directionally, pointing opposite to \(\vec{p}\).

3. Why does the equatorial field decrease as [\dfrac{1}{r^3}]?

Because dipole field is derived from the difference of two point-charge fields, leading to a higher power dependence on r.

4. Why is the equatorial field weaker than the axial field?

Because on the equatorial line, fields partially cancel; on axial line they add fully.

5. Why is the dipole moment important for equatorial field?

Because the equatorial field depends entirely on p, not on q or a individually.

6. Why do we use far-field approximation?

It simplifies formulae and is valid when r is much greater than dipole length.

7. Why do vertical components of electric field add?

Both charges produce vertical components that point in the same direction.

8. Why is the equatorial point equidistant from both charges?

Because it lies on the perpendicular bisector of the dipole.

9. What happens to equatorial field if dipole moment is doubled?

The equatorial field also doubles since \[E \propto p\].

10. Can equatorial field ever become zero?

Only at infinite distance or if dipole moment p = 0.

11. What happens to equatorial field very close to dipole?

It increases sharply due to smaller denominator \[(a^2 + r^2)^{3/2}\].

12. Why is field direction opposite to p even when p is positive?

Dipole moment direction is defined from –q to +q, but net equatorial field points toward –q, opposite to p.

13. Does equatorial field depend on charge sign?

No; magnitude depends on p. Direction is determined by dipole orientation.

14. Does medium affect equatorial field?

Yes, replace \[\varepsilon_0\] by \[\varepsilon\], decreasing the field.

15. How does equatorial field compare with other dipoles?

Stronger dipole moment → stronger equatorial field for same r.

7. FAQ / Common Misconceptions (10)

1. Is equatorial field equal to field of a point charge?

No. It varies as \[\dfrac{1}{r^3}\], not \[\dfrac{1}{r^2}\].

2. Is equatorial field always pointing outward?

No. It is always opposite to dipole moment.

3. Do horizontal components ever add?

No. They always cancel by symmetry.

4. Is equatorial field always half of axial field?

Only at **far distances**.

5. Does equatorial field depend on sign of individual charges?

No. Only magnitude of p matters.

6. Does distance from dipole center matter?

Yes. Field sharply decreases with r.

7. Can equatorial field point along dipole moment?

No. It always opposes \(\vec{p}\).

8. Is equatorial field uniform?

No. It varies strongly with r.

9. Is field zero at midpoint of dipole?

No. Axial field is zero at midpoint, not equatorial.

10. Does reversing dipole orientation change magnitude?

No. Only direction of field reverses.

8. Practice Questions (With Step-by-Step Solutions)

Q1.

Dipole moment [p = 2\times10^{-7}\ \text{C·m}]. Find equatorial field at [r = 20\ \text{cm}].

Solution:

[E] [= \dfrac{1}{4\pi\varepsilon_0}\cdot\dfrac{p}{r^3}]

[E] [= 9\times10^9 \cdot \dfrac{2\times10^{-7}}{(0.20)^3}]

[= 9\times10^9 \cdot \dfrac{2\times10^{-7}}{0.008}]

[= 9\times10^9 \cdot 2.5\times10^{-5}]

[E] [= 2.25\times10^{5}\ \text{N/C}]

Q2.

Find the equatorial field at a distance 10 cm for [p = 1\times10^{-8}\ \text{C·m}].

Solution:

[E] [= 9\times10^9 \cdot\dfrac{1\times10^{-8}}{(0.10)^3}]

[= 9\times10^9 \cdot\dfrac{10^{-8}}{10^{-3}}]

[

= 9\times10^9 \cdot10^{-5}

]

[

E = 9\times10^{4}\ \text{N/C}

]

Q3.

For a dipole, compare equatorial fields at 5 cm and 10 cm.

Solution:

[

E\propto\dfrac{1}{r^3}

]

[\dfrac{E_1}{E_2}=\left(\dfrac{r_2}{r_1}\right)^3]

[

= \left(\dfrac{0.10}{0.05}\right)^3 = 8

]

Thus,

[

E_{5\text{cm}} = 8E_{10\text{cm}}

]

Q4.

A dipole has [p = 5\times10^{-9}]. Find equatorial field at [r = 50\ \text{cm}].

Solution:

[E] [= 9\times10^9 \cdot\dfrac{5\times10^{-9}}{(0.50)^3}]

[

= 9\times10^9 \cdot\dfrac{5\times10^{-9}}{0.125}

]

[

= 9\times10^9 \cdot 4\times10^{-8}

]

[

= 3.6\times10^{2}\ \text{N/C}

]

Q5.

For dipole with [p = 3\times10^{-7}], find equatorial field at 30 cm.

Solution:

[E] [= 9\times10^9 \cdot\dfrac{3\times10^{-7}}{(0.30)^3}]

[

= 9\times10^9 \cdot\dfrac{3\times10^{-7}}{0.027}

]

[

= 9\times10^9 \cdot 1.11\times10^{-5}

]

[

= 10^{5}\ \text{N/C (approx)}

]