Physics and Mathematics

Moment of Inertia of a Uniform Hollow Sphere about a Diameter

1. Concept Overview

A uniform hollow sphere (thin spherical shell) has all its mass distributed on a spherical surface of radius [R]. The moment of inertia about any diameter (an axis through the center) measures the resistance of the shell to angular acceleration about that axis.

2. Final Result (to remember)

[ I = \dfrac{2}{3} M R^2 ]

(where [M] is the total mass and [R] is the radius of the hollow sphere)

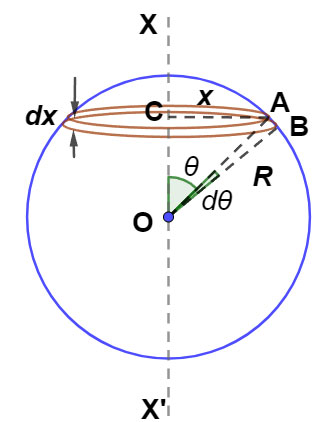

3. Derivation (using ring method)

- Consider the hollow sphere of radius [R] and total mass [M]. Surface mass density:

[ \sigma = \dfrac{M}{4\pi R^2} ]

- Slice the sphere into thin coaxial rings (latitude rings) at polar angle [\theta] (measured from the axis).

- Radius of a ring = [R\sin\theta]

- Width of ring (arc) = [R d\theta]

- Circumference of ring = [2\pi R\sin\theta]

- Area of ring ≈ [2\pi R\sin\theta \cdot R,d\theta = 2\pi R^2\sin\theta d\theta]

Image Credit: Ucale.org

- Mass of the ring:

[ dm = \sigma \cdot 2\pi R^2 \sin\theta d\theta] [= 2\pi\sigma R^2 \sin\theta d\theta ]

- Moment of inertia of the ring about the axis (treat ring as thin loop of radius [R\sin\theta]):

[ dI = (R\sin\theta)^2 dm] [= R^2\sin^2\theta \cdot 2\pi\sigma R^2 \sin\theta d\theta] [= 2\pi\sigma R^4 \sin^3\theta d\theta ]

- Integrate over [\theta] from [0] to [\pi]:

[ I = \int_0^\pi 2\pi\sigma R^4 \sin^3\theta d\theta] [= 2\pi\sigma R^4 \int_0^\pi \sin^3\theta d\theta ]

Recall:

[ \int_0^\pi \sin^3\theta d\theta = \tfrac{4}{3} ]

So,

[ I = 2\pi\sigma R^4 \cdot \dfrac{4}{3}] [= \dfrac{8\pi}{3} \sigma R^4 ]

Substitute [ \sigma = \dfrac{M}{4\pi R^2} ]:

[ I = \dfrac{8\pi}{3} \cdot \dfrac{M}{4\pi R^2} \cdot R^4] [= \dfrac{2}{3} M R^2 ]

Thus:

[ \boxed{ I = \dfrac{2}{3} M R^2 } ]

4. Key Features

- Valid for a thin spherical shell (mass concentrated on the surface).

- Moment of inertia is the same about any diameter due to spherical symmetry.

- Compare with solid sphere: [ I_{\text{solid}} = \dfrac{2}{5} M R^2 ] — hollow sphere has larger [I] for same [M,R].

5. Important Formulas to Remember

| Formula | Description |

|---|---|

| [ I = \dfrac{2}{3} M R^2 ] | Moment of inertia of a thin hollow sphere about a diameter (center axis). |

| [ \sigma = \dfrac{M}{4\pi R^2} ] | Surface mass density of a thin spherical shell. |

| [ I_{\text{solid}} = \dfrac{2}{5} M R^2 ] | Moment of inertia of a solid (uniform) sphere — useful comparison. |

| [ I_{\text{tangent}} = I + M R^2 = \dfrac{5}{3} M R^2 ] | Moment of inertia about a tangent (by Parallel Axis Theorem). |

6. Conceptual Questions

1. Why is the moment of inertia of a hollow sphere larger than that of a solid sphere of the same mass and radius?

Because in a hollow sphere the mass is concentrated at the outer radius [R], increasing distances [r] in [I=\int r^2 dm], whereas in a solid sphere mass also lies closer to the axis.

2. Does the moment of inertia of a hollow sphere depend on the axis chosen through the center?

No — due to spherical symmetry, the moment of inertia about any diameter (axis through center) is the same.

3. What is the role of surface density [\sigma] in the derivation?

[\sigma] converts geometric area elements into mass elements [dm] for integration over the shell.

4. How would the M.I. change if the shell were thicker (finite thickness)?

For finite thickness you would integrate through the radial thickness; result approaches solid sphere when inner radius → 0.

5. How does the ring-method (slicing into rings) simplify the calculation?

Each latitude ring has a simple M.I. (like a loop), allowing reduction from 2D surface integral to a single-variable integral.

6. Is [I = \tfrac{2}{3}MR^2] valid if the mass distribution is non-uniform on the shell?

No — it assumes uniform surface density; non-uniform distribution requires recalculating [dm].

7. Which contributes more to I: mass near the equator or near the poles?

Mass near the equator (larger [r = R\sin\theta]) contributes more because [r^2] weighting.

8. How would you obtain the moment of inertia about a tangent to the sphere?

Use Parallel Axis Theorem: [I_{\text{tangent}} = I_{CM} + MR^2 = \tfrac{2}{3}MR^2 + MR^2 = \tfrac{5}{3}MR^2].

9. Why is symmetry important when choosing integration coordinates?

Symmetry reduces integrals to one variable (here [\theta]) and avoids vector components canceling complexities.

10. What physical systems approximate a thin hollow sphere?

Examples: thin-walled metal shells, hollow sports balls (idealized), spherical lampshades.

11. If we double the radius but keep mass constant, how does I change?

[I \propto R^2], so I becomes 4× larger.

12. If we double the mass but keep radius constant, how does I change?

[I \propto M], so I doubles.

13. Can a hollow sphere have zero moment of inertia?

No, unless mass or radius is zero.

14. How does the shell’s moment of inertia affect rotational kinetic energy?

Rotational kinetic energy: [K = \tfrac{1}{2}I\omega^2], so larger I stores more rotational energy at same [\omega].

15. Why is the integral of [\sin^3\theta] equal to [\tfrac{4}{3}] over [0\to\pi]?

This is a standard trigonometric integral; it follows from reduction identities or substitution.

7. FAQ / Common Misconceptions

1. Does the hollow sphere behave like a ring in terms of I?

Not exactly — a ring is 1D mass around a circle; a hollow sphere is 2D surface distributed over angles, producing [I=\tfrac{2}{3}MR^2], different from a ring’s [I=MR^2].

2. Is [I] independent of axis orientation?

Only for axes through the center (any diameter). For axes not through the center, use Parallel Axis Theorem.

3. Will a hollow sphere always rotate slower than a solid sphere of same mass and radius for same applied torque?

Not necessarily — angular acceleration depends on torque vs I. Since hollow sphere has larger I than a solid sphere of same M,R, it will have smaller angular acceleration for the same torque.

4. Is the derived [I] approximate?

No — it is an exact analytical result under the thin-shell (uniform surface) assumption.

5. Does thickness negligible mean massless thickness?

No — “thin” means thickness ≪ R so radial variation is ignored; total mass is still M distributed over shell surface.

8. Practice Questions (with solutions)

Q1. A thin hollow sphere of mass [M = 3.0\ \text{kg}] and radius [R = 0.5\ \text{m}] rotates with angular speed [\omega = 10\ \text{rad/s}]. Find its rotational kinetic energy.

Solution:

[ I = \dfrac{2}{3}MR^2] [= \dfrac{2}{3}\times 3.0 \times (0.5)^2] [= \dfrac{2}{3}\times 3.0 \times 0.25] [= \dfrac{2}{3}\times 0.75 = 0.5\ \text{kg·m}^2 ]

[ K = \tfrac{1}{2} I \omega^2] [= \tfrac{1}{2}\times 0.5 \times 10^2] [= 0.25 \times 100 = 25\ \text{J} ]

Q2. Compare moments of inertia of a hollow sphere and a solid sphere of same mass [M] and radius [R]. Which has greater I and by what factor?

Solution:

Hollow: [ I_h = \dfrac{2}{3}MR^2 ]

Solid: [ I_s = \dfrac{2}{5}MR^2 ]

Ratio: [ \dfrac{I_h}{I_s} = \dfrac{2/3}{2/5}] [= \dfrac{5}{3} \approx 1.666\ldots ]

So hollow sphere has [ \tfrac{5}{3} ] times the I of the solid sphere.

Q3. A thin hollow sphere of mass [2 kg] and radius [0.4 m] is free to rotate about a tangent. Find its moment of inertia about the tangent.

Solution:

First, [ I_{CM} = \dfrac{2}{3}MR^2] [= \dfrac{2}{3}\times 2\times (0.4)^2] [= \dfrac{4}{3}\times 0.16] [= \dfrac{4}{3}\times 0.16] [= 0.2133\ldots\ \text{kg·m}^2 ]

Parallel Axis Theorem: [ I_{\text{tangent}} = I_{CM} + MR^2] [= 0.2133\ldots + 2\times 0.16] [= 0.2133\ldots + 0.32 = 0.5333\ldots\ \text{kg·m}^2 ]

(Or use exact fractions: [ I_{CM} = \tfrac{2}{3}\cdot 2\cdot 0.16] [= \tfrac{64}{300} = \tfrac{16}{75} \approx 0.2133 ]; [ I_t = \tfrac{16}{75}+0.32] [= \tfrac{16}{75} + \tfrac{32}{100} = \ldots ])

Q4. A hollow sphere (mass [M], radius [R]) rolls without slipping down an incline. Express the fraction of gravitational potential energy that becomes translational kinetic energy at the bottom.

Solution (symbolic):

Total energy: [ Mgh ] converts into translational [ \tfrac{1}{2} M v^2 ] + rotational [ \tfrac{1}{2} I \omega^2 ]. With pure rolling: [ \omega = v/R ], and [ I = \tfrac{2}{3} M R^2 ].

Rotational energy: [ \tfrac{1}{2} I \omega^2] [= \tfrac{1}{2}\cdot \tfrac{2}{3}MR^2 \cdot \dfrac{v^2}{R^2}] [= \dfrac{1}{3} M v^2 ].

Total kinetic: [ \tfrac{1}{2} M v^2 + \dfrac{1}{3} M v^2] [= \dfrac{5}{6} M v^2 ].

So [ Mgh = \dfrac{5}{6} M v^2 \Rightarrow v^2] [= \dfrac{6}{5} gh ].

Fraction into translational KE: [ \dfrac{\tfrac{1}{2} M v^2}{Mgh}] [= \dfrac{\tfrac{1}{2} v^2}{gh}] [= \dfrac{\tfrac{1}{2}\cdot \dfrac{6}{5}}{1}] [= \dfrac{3}{5} ].

Hence 3/5 of potential energy becomes translational kinetic energy.

Q5. A hollow sphere of mass [M = 4 kg] and radius [R = 0.25 m] has angular momentum [L = 2\ \text{kg·m}^2/\text{s}] about a diameter. Find the angular speed [\omega].

Solution:

[ I = \dfrac{2}{3} M R^2] [= \dfrac{2}{3}\times 4 \times (0.25)^2] [= \dfrac{8}{3}\times 0.0625] [= \dfrac{8}{3}\times \dfrac{1}{16}] [= \dfrac{8}{48}] [= \dfrac{1}{6}\ \text{kg·m}^2 \approx 0.1666667 ]

[ L = I\omega \Rightarrow \omega] [= \dfrac{L}{I} = \dfrac{2}{1/6}] [= 12\ \text{rad/s} ]