Physics and Mathematics

Poiseuille’s Formula

1. Statement of the Law

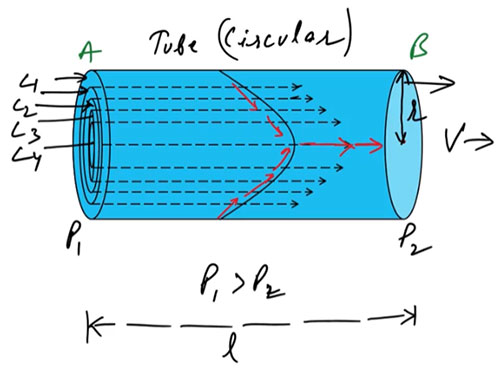

Poiseuille’s Law (or Poiseuille’s Equation) describes the steady, laminar flow of an incompressible, viscous fluid through a cylindrical pipe.

It states that:

The rate of flow of liquid through a capillary tube is directly proportional to the pressure difference and the fourth power of the radius of the tube, and inversely proportional to the viscosity and length of the tube.

Mathematically,

[Q] [= \dfrac{\pi r^4 (P_1 – P_2)}{8 \eta l}]

Where:

- [Q] = Volume flow rate

- [r] = Radius of the tube

- [l] = Length of the tube

- [\eta] = Coefficient of viscosity

- [P_1 – P_2] = Pressure difference across the two ends

2. Explanation and Mathematical Derivation

Consider a cylindrical tube of radius [r] and length [l].

A pressure difference [(P_1 – P_2)] drives the fluid from one end to another.

Let us take a thin cylindrical layer of radius [x] and thickness [dx].

Velocity of the layer = [v(x)]

The viscous force on this layer (due to the outer slower layer) is:

[dF = -\eta (2\pi x l) \dfrac{dv}{dx}]

In steady state, this viscous force balances the pressure force:

[dF = x^2 \pi (P_1 – P_2)]

Equating and simplifying:

[\dfrac{dv}{dx}] [= -\dfrac{(P_1 – P_2)}{4 \eta l} x]

Integrating:

[v] [= \dfrac{(P_1 – P_2)}{4 \eta l} (r^2 – x^2)]

Hence, velocity distribution is parabolic, maximum at the center ([x = 0]) and zero at the walls ([x = r]).

Maximum velocity:

[v_{max}] [= \dfrac{(P_1 – P_2) r^2}{4 \eta l}]

Average velocity:

[v_{avg}] [= \dfrac{v_{max}}{2}]

Now, Volume flow rate:

[Q] [= \int_0^r 2\pi x v(x) dx] [= \dfrac{\pi (P_1 – P_2) r^4}{8 \eta l}]

3. Dimensions and Units

| Quantity | Symbol | SI Unit | Dimensions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient of viscosity | [\eta] | Pa·s | [M L^{-1} T^{-1}] |

| Volume flow rate | [Q] | m³/s | [L³ T⁻¹] |

| Pressure difference | [P_1 – P_2] | N/m² | [M L⁻¹ T⁻²] |

4. Key Features

- Valid only for laminar flow (Reynolds number < 2000).

- Flow rate is highly sensitive to radius ([r⁴] dependence).

- Flow rate inversely depends on viscosity and length.

- Applicable for narrow tubes and steady-state flow.

- The velocity profile is parabolic, not uniform.

- Used to study blood flow, oil pipelines, and capillary flow.

5. Important Formulas to Remember

| Formula | Description |

|---|---|

| [v(x)] [= \dfrac{(P_1 – P_2)}{4 \eta l} (r^2 – x^2)] | Velocity at distance [x] from axis |

| [v_{max}] [= \dfrac{(P_1 – P_2) r^2}{4 \eta l}] | Maximum velocity at center |

| [v_{avg}] [= \dfrac{v_{max}}{2}] | Average velocity |

| [Q] [= \dfrac{\pi r^4 (P_1 – P_2)}{8 \eta l}] | Volume flow rate |

| [\Delta P] [= \dfrac{8 \eta l Q}{\pi r^4}] | Pressure drop relation |

6. Conceptual Questions with Solutions

1. Why is the flow rate proportional to the fourth power of the radius?

Because a small increase in radius allows many more layers of fluid to move with higher velocity due to reduced viscous drag, leading to [Q ∝ r⁴].

2. Why is the velocity maximum at the center of the tube?

Because at the center there is no contact with walls, hence no viscous resistance, making the velocity maximum.

3. What happens to flow rate if the length of the tube is doubled?

Flow rate becomes half, since [Q ∝ \dfrac{1}{l}].

4. What happens to flow rate if viscosity increases?

Flow rate decreases because [Q ∝ \dfrac{1}{\eta}].

5. Why does Poiseuille’s law not apply to turbulent flow?

Because it assumes laminar motion with smooth layers; turbulence causes chaotic velocity fluctuations invalidating the assumptions.

6. What does a parabolic velocity profile indicate?

It indicates laminar flow where each layer moves smoothly with different velocities.

7. Why is velocity zero at the pipe walls?

Due to the **no-slip condition**, the fluid layer in contact with the wall is stationary relative to it.

8. Does pressure remain constant along the pipe?

No. Pressure decreases linearly along the pipe due to viscous energy losses.

9. How does temperature affect flow rate?

Viscosity decreases with temperature; hence, flow rate increases as temperature rises.

10. Can Poiseuille’s law be applied to gases?

Yes, if the flow is steady, laminar, and the gas behaves as an incompressible fluid under small pressure gradients.

11. Why do narrow blood capillaries have higher resistance?

Because resistance varies inversely with [r⁴]; hence very small radii lead to high resistance.

12. How is energy lost in viscous flow?

Energy is lost as heat due to internal friction between adjacent fluid layers.

13. What is meant by laminar flow?

It is smooth, orderly motion of fluid layers parallel to each other without mixing.

14. How can laminar flow be ensured experimentally?

By maintaining a low flow velocity so that Reynolds number < 2000.

15. Why is the flow rate so sensitive to tube radius?

Because of the [r⁴] dependence — even small radius changes greatly influence the flow rate.

7. FAQ / Common Misconceptions

1. Is Poiseuille’s law valid for all fluids?

No, only for **Newtonian fluids** where viscosity remains constant.

2. Does flow start instantly when pressure is applied?

No, it takes a short time to reach steady-state laminar flow.

3. Is the velocity same across the cross-section?

No, it varies parabolically — maximum at the center and zero at the walls.

4. Can flow continue without pressure difference?

No, a pressure difference is essential to drive flow.

5. Is viscosity independent of temperature?

No, viscosity decreases as temperature increases for liquids.

6. Why doesn’t fluid slip on the wall?

Because of adhesive molecular interactions causing the no-slip boundary condition.

7. What happens when Reynolds number exceeds 2000?

Flow becomes turbulent, invalidating Poiseuille’s equation.

8. Is pressure drop linear along the pipe?

Yes, under steady laminar flow conditions.

9. Do wider pipes always reduce energy loss?

Yes, because pressure drop is inversely proportional to [r⁴].

10. Why is this law important in biology?

It helps explain **blood flow** in arteries and veins, where pressure, viscosity, and vessel radius affect circulation.

8. Practice Questions (with Step-by-Step Solutions)

Q1. A fluid of viscosity [0.01 \ Pa·s] flows through a tube of radius [0.005 \ m] and length [0.5 \ m]. Find the rate of flow when pressure difference is [2 \times 10^3 \ Pa].

Solution:

[Q] [= \dfrac{\pi r^4 (P_1 – P_2)}{8 \eta l}]

[= \dfrac{3.14 (5 \times 10^{-3})^4 (2 \times 10^3)}{8 \times 0.01 \times 0.5}] [= 4.9 \times 10^{-6} \ m^3/s]

Q2. If the radius of the pipe is doubled, how does the flow rate change?

Solution:

[Q ∝ r^4] [⇒ Q’/Q = (2r)^4 / r^4] [= 16]

Hence, flow rate increases 16 times.

Q3. A capillary of radius [0.3 , mm] and length [0.2 , m] carries water under pressure difference [100 , Pa]. Find the volume flow rate if [\eta = 1.0 \times 10^{-3} , Pa·s].

Solution:

[Q] [= \dfrac{\pi (0.3 \times 10^{-3})^4 (100)}{8 (1.0 \times 10^{-3})(0.2)}] [= 1.6 \times 10^{-10} \ m^3/s]

Q4. The pressure difference between two ends of a pipe is 400 Pa and flow rate is [2 \times 10^{-6} \ m^3/s]. If the length is doubled, find new flow rate.

Solution:

[Q ∝ \dfrac{1}{l}] [⇒ Q’ = Q/2] [= 1 \times 10^{-6} \ m^3/s]

Q5. How does viscosity affect flow in the human body?

Solution:

Higher blood viscosity (due to dehydration or disease) reduces flow rate, increasing pressure load on the heart — consistent with Poiseuille’s Law.