Physics and Mathematics

Refraction on the Basis of Wave Theory

1. Concept Overview

When a wave (e.g., light) travels from one medium into another (say from air into water), its direction generally changes — this bending is called refraction.

A simple way to understand why this bending happens is Huygens’ principle: every point on an incoming wavefront acts like a small source of spherical secondary wavelets. The new wavefront in the second medium is the envelope (tangent) to all those secondary wavelets. If the speed of the wave is different in the two media, the secondary wavelets grow at different rates and the envelope (i.e., the new wavefront) is tilted — that tilt is exactly the bending we call refraction.

In plain words:

- Light goes slower (or faster) in the new medium.

- Because parts of the wavefront enter the new medium earlier than others, those parts “lag” (or “lead”) relative to the rest.

- The envelope of all tiny wavelets in the denser medium is tilted, producing a refracted ray.

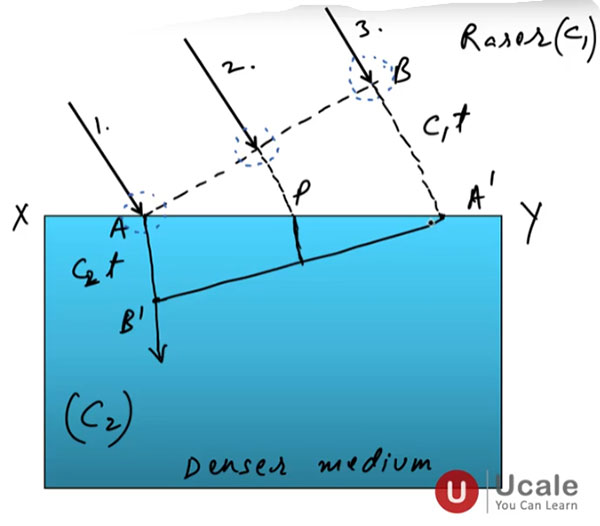

2. Explanation and Mathematical Derivation (using your image points A, A′, B, B′, C)

- The horizontal line X–Y is the boundary between the two media. Above X–Y is medium (C_1) (speed (v_1)), below X–Y is medium (C_2) (speed (v_2)). The lower medium is the denser medium in the image.

- Two nearby points on an incident wavefront meet the interface at A and A′ respectively (A at the left, A′ at the right on X–Y).

- The corresponding points on the wavefront just above the interface are labeled B (above A) and the other farther right (not explicitly labeled on top in the cropped figure) — the image shows three incident wave rays (1,2,3) for intuition.

- Points B′ and C indicate points inside the denser medium to which the secondary wavelets from A and A′ grow during the same time interval.

We now follow the Huygens construction exactly as in the diagram:

- Pick two successive points on the same incident wavefront that strike the interface at points (A) and (A’) on the line (X!-!Y).

- Suppose the point at (A’) reaches the interface slightly later than the point at (A). Let the time taken for this small advance be (t). (This is the same short time shown implicitly in your diagram — during (t) the parts of the wavefront move the distances indicated by dashed/solid arcs.)

- In time (t):

- The part of the wavefront still in the first medium (just above the interface) moves forward a distance (v_1 t). The projection of that forward motion along the interface contributes to the lateral separation between the foot points (A) and (A’).

- Meanwhile, the secondary wavelet launched from the point (A) into the denser medium expands as a circle (or sphere in 3D) of radius (v_2 t). The envelope (tangent) to these wavelets inside the denser medium determines where the refracted wavefront will be after time (t).

- From the geometry (right triangles formed by the normal at (A) and the two traveled distances), you obtain the relations (see the right triangles in your image connecting (A), (A’), and the centers of the wavelets):

[\text{(projection along interface)}] [= v_1 t \sin i = v_2 t \sin r .]

Therefore (cancel (t)),

[\boxed{\dfrac{\sin i}{\sin r} = \dfrac{v_1}{v_2}}]

(Explanation of symbols used here in the image)

- (i) is the angle of incidence (angle between incident ray and the normal at (A)), visible in your diagram near (A).

- (r) is the angle of refraction (angle between refracted ray inside the denser medium and the normal), visible in your diagram near the interior ray (the line that goes down-right from A to the interior point).

- Using the definition of refractive index (n) (relative to vacuum speed (c)), (n = \dfrac{c}{v}), we can rewrite the velocity ratio as:

[\dfrac{v_1}{v_2} = \dfrac{c/n_1}{c/n_2}] [= \dfrac{n_2}{n_1}]

Substituting into the previous expression gives the familiar Snell’s law:

[\boxed{n_1 \sin i = n_2 \sin r}]

This is exactly what the Huygens construction (with points (A, A’, B, B’, C) in your figure) yields: the geometry of growing wavelets gives [\sin i / \sin r = v_1 / v_2], which is equivalent to [n_1\sin i = n_2 \sin r].

3. Dimensions and Units

- Angles (i) and (r): dimensionless (units: degrees or radians).

- Speeds [v_1, v_2]: [LT^{-1}] (SI unit: m/s).

- Refractive index (n): dimensionless.

4. Key Features / Physical Insights

- Refraction occurs because wave speed changes when waves enter a different medium; parts of the wavefront enter earlier and re-form the front by Huygens’ construction.

- Huygens’ construction produces Snell’s law directly: ([n_1\sin i = n_2\sin r]).

- If [v_2 < v_1] (wave slows down in medium 2), the ray bends toward the normal [r < i].

- If [v_2 > v_1] (wave speeds up), the ray bends away from the normal.

- The frequency of the wave stays constant across the boundary; wavelength and speed change so that [v = \lambda f].

5. Important Formulas to Remember

| Quantity | Formula |

|---|---|

| Snell’s law | [n_1 \sin i = n_2 \sin r] |

| Velocity ratio form | [\displaystyle \frac{\sin i}{\sin r} = \frac{v_1}{v_2}] |

| Refractive index | [n = \dfrac{c}{v}] |

| Wavelength change | [ \lambda_2 = \dfrac{v_2}{v_1} \lambda_1] (since (f) constant) |

6. Conceptual Questions with Solutions

1. Why does the ray bend when entering a different medium?

Because the speed of wave propagation changes in the new medium; parts of the wavefront enter earlier and produce a new tilted envelope (Huygens’ principle).

2. Why does frequency remain constant across the boundary?

Frequency is set by the source and cannot change instantaneously at the boundary; energy continuity and boundary conditions force the same oscillation rate on both sides.

3. If light goes from air to glass, does it bend toward or away from the normal?

Glass is denser (smaller [v]), so the ray bends **toward** the normal (i.e., [r < i]).

4. How is Snell’s law derived from Huygens’ principle?

By considering two nearby points on a wavefront (A and A′) and using the distances traveled by wavelets in time \(t\) in each medium, geometry gives [\sin i / \sin r = v_1 / v_], which with [n=c/v] yields [n_1\sin i=n_2\sin r].

5. Can the refracted ray be on the original side (i.e., no refraction)?

Only if speeds are equal in both media [v_1=v_2]; then [i=r] and there’s no refraction.

6. What happens at grazing incidence [i\to90^\circ]?

If [i\to90^\circ] and [v_2<v_1], the refracted angle may still be less than [90^\circ]; if the opposite, total internal reflection can occur (see below).

7. Why does wavelength change at the boundary?

Because [v=\lambda f] and [f] is unchanged, so if speed [v] decreases, wavelength [\lambda] decreases proportionally.

8. Does refraction always bend toward the normal when entering a denser medium?

Yes, if the refractive index increases [n_2>n_1], then [\sin r = (n_1/n_2)\sin i] is smaller, so [r<i], i.e., bending toward normal.

9. Can Huygens’ principle predict total internal reflection?

Yes: when light tries to go from denser to rarer medium, the constructed geometry can fail to produce a real refracted wave if [\sin r > 1]; then no real refracted wave exists and total internal reflection results.

10. In the uploaded image, what are B and B′?

In the image, [B] is a point on the incident wavefront above the interface corresponding to [A], and [B’] is the point inside the denser medium directly below A where a secondary wavelet expands.

11. Why do we equate lateral displacements along the interface in the derivation?

Because during the same time interval [t] the lateral progress (projection along the surface) of the incident front and the projection due to the secondary wavelet must correspond to the same surface separation [AA’]. That equality yields the relation between [\sin i] and [\sin r].

12. Does the intensity of light change on refraction?

Some intensity may be reflected and some transmitted; amplitude (and thus intensity) depends on boundary conditions and material properties (Fresnel relations).

13. If a wave speeds up in the second medium, which way does it bend?

It bends away from the normal (i.e., [r>i]).

14. Does refraction depend on wavelength (color)?

Yes: refractive index typically depends on wavelength (dispersion); different colors refract by different amounts.

15. Can Huygens’ principle be applied to sound waves?

Yes. Huygens’ idea is general to waves; refraction of sound at interfaces of different media is explained similarly.

7. FAQ / Common Misconceptions (10)

1. “Refraction means light slows down permanently.”

No. The speed changes only while the light is inside the medium. Once it emerges to the original medium, it resumes the original speed.

2. “Refraction violates conservation of energy.”

No. Energy is conserved; only direction, wavelength and speed change; some energy may be reflected or absorbed.

3. “Ray diagrams contradict Huygens’ principle.”

No. Rays are simply normals to wavefronts; Huygens’ construction and ray optics are consistent.

4. “Refraction always decreases wavelength.”

Not always; wavelength decreases if speed decreases; if speed increases, wavelength increases.

5. “Frequency changes at the boundary.”

No—the frequency remains fixed by the source.

6. “Snell’s law is empirical only.”

It was empirical historically, but Huygens’ construction provides a theoretical wave-based derivation and Maxwell’s equations provide the full electromagnetic description.

7. “All wavelengths refract the same.”

No—due to dispersion, different wavelengths have different refractive indices.

8. “Refraction only occurs for light.”

No. Any wave (sound, water) refracts when crossing into a medium with a different wave speed.

9. “Refraction direction depends on amplitude.”

No. Direction depends only on geometry and speeds (i.e., refractive indices).

10. “If the wavefront is curved, Snell’s law doesn’t apply.”

Snell’s law applies locally: for a small patch of a curved wavefront, the same local construction yields the same relation between local incidence and refraction angles.

8. Practice Questions (with Step-by-Step Solutions)

Q1. Light passes from air [n_1\approx1.00] into glass [n_2=1.5]. If [i=30^\circ], find [r].

Solution:

[n_1\sin i = n_2 \sin r] [\Rightarrow \sin r = \dfrac{n_1}{n_2}\sin i] [= \dfrac{1.00}{1.50}\sin30^\circ] [= \dfrac{1}{1.5}\times 0.5] [= \dfrac{1}{3}]

[r] [= \arcsin\left(\tfrac{1}{3}\right)] [\approx 19.47^\circ]

Q2. Using your image’s geometry: if [v_1=3.0\times10^8] m/s and [v_2=2.0\times10^8] m/s, and [i=45^\circ], find [r].

Solution:

[\dfrac{\sin i}{\sin r}=\dfrac{v_1}{v_2}] [=\dfrac{3.0\times10^8}{2.0\times10^8}] [=1.5]

[\sin r = \dfrac{\sin i}{1.5}] [=\dfrac{\sin45^\circ}{1.5}] [=\dfrac{0.7071}{1.5}] [=0.4714]

[r=\arcsin(0.4714)] [\approx 28.1^\circ]

Q3. If a wave has wavelength [\lambda_1=600] nm in medium 1 and it enters medium 2 where [v_2/v_1=0.75], what is [\lambda_2]?

Solution:

[\lambda_2=\dfrac{v_2}{v_1}\lambda_1] [=0.75\times 600 \text{nm}] [=450 \text{nm}]

Q4. Explain using Huygens why at a shallow enough angle a ray leaving a denser medium experiences total internal reflection.

Solution:

As incidence angle (i) increases, [\sin r=(n_1/n_2)\sin i] increases. If [n_1<n_2] (coming from denser to rarer), there is a critical [i_c] where [\sin r = 1]; beyond that no real [r] exists → no refracted wave; Huygens’ construction cannot form a forward envelope, so the wave is totally internally reflected.

[\sin i_c = \dfrac{n_2}{n_1}\cdot 1] [\quad] [\text{(use appropriate ordering of n’s)}]

Q5. Using the picture points: during time [t], A′ advances a distance [v_1 t] in medium 1 while the secondary wavelet from A grows radius [v_2 t] in medium 2. Show that the lateral shift along the boundary is the same in both constructions and leads to Snell’s law.

Solution (sketch):

- The lateral (tangential) component of the distance [v_1 t] traveled by the front in medium [C_1] equals [v_1 t \sin i].

- The lateral component of the secondary wavelet of radius [v_2 t] equals [v_2 t \sin r].

- These lateral distances match the same interface separation [AA’] (see the figure), so [v_1\sin i = v_2\sin r], giving [\sin i/\sin r = v_2/v_1]. Using [n=c/v] delivers [n_1\sin i = n_2\sin r].