Physics and Mathematics

Terminal Velocity

1. Statement of the Concept

When a body (like a raindrop or a small sphere) falls freely through a viscous fluid, it initially accelerates due to gravity. As its velocity increases, the viscous drag and buoyant forces also increase. Eventually, these opposing forces balance the weight of the body, and it moves with a constant velocity.

This steady velocity is known as the Terminal Velocity.

2. Explanation and Mathematical Derivation

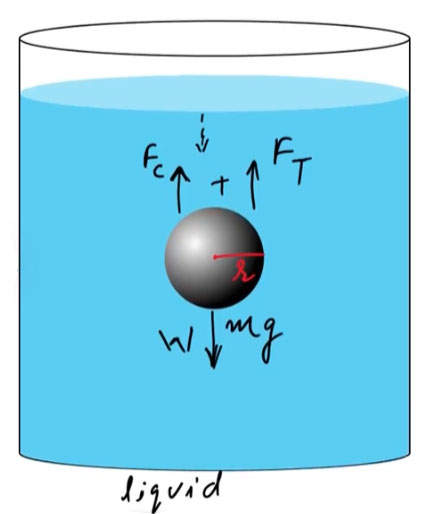

Let a small sphere of radius [r], density [ρ_s], be falling through a viscous fluid of density [ρ] and coefficient of viscosity [η].

Forces acting on the sphere:

- Weight of the sphere: [W = \dfrac{4}{3}πr^3ρ_s g]

- Buoyant force: [F_B = \dfrac{4}{3}πr^3ρ g]

- Viscous force (Stokes’ drag): [F_V = 6πrηv]

At terminal velocity ([v_t]), the sphere falls with uniform velocity, so the net force = 0:

[

W = F_B + F_V

]

Substitute the expressions:

[\dfrac{4}{3}πr^3ρ_s g] [= \dfrac{4}{3}πr^3ρ g + 6πrηv_t]

Simplifying:

[v_t] [= \dfrac{2r^2(ρ_s – ρ)g}{9η}]

Hence,

[{v_t ∝ r^2}], [\quad] [v_t ∝ (ρ_s – ρ)], [\quad] [v_t ∝ \dfrac{1}{η}]

3. Dimensions and Units

| Quantity | Symbol | Dimensions | SI Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Terminal velocity | [v_t] | [L T⁻¹] | m/s |

| Radius of sphere | [r] | [L] | m |

| Coefficient of viscosity | [η] | [M L⁻¹ T⁻¹] | N·s/m² or Pa·s |

| Density difference | [(ρ_s – ρ)] | [M L⁻³] | kg/m³ |

| Acceleration due to gravity | [g] | [L T⁻²] | m/s² |

4. Key Features

- Terminal velocity is attained when the downward and upward forces become equal.

- It depends directly on the square of the radius of the sphere.

- It is greater in air (low viscosity) and smaller in liquids (high viscosity).

- For two spheres of radii [r₁] and [r₂],

[\dfrac{v_{t1}}{v_{t2}}] [= \left(\dfrac{r_1}{r_2}\right)^2]. - Rain drops attain terminal velocity before reaching the ground — preventing damage despite their height of fall.

5. Important Formulas to Remember

| Formula | Description |

|---|---|

| [v_t] [= \dfrac{2r^2(ρ_s – ρ)g}{9η}] | Terminal velocity of a sphere |

| [F_V] [= 6πrηv] | Stokes’ viscous drag |

| [W] [= \dfrac{4}{3}πr^3ρ_s g] | Weight of the sphere |

| [F_B] [= \dfrac{4}{3}πr^3ρ g] | Buoyant force |

| [v_t ∝ \dfrac{1}{η}] | Terminal velocity inversely proportional to viscosity |

6. Conceptual Questions with Solutions

1. Why does a sphere not continue accelerating indefinitely when falling through a viscous liquid?

Because viscous and buoyant forces increase with velocity until they balance the weight of the sphere, leading to zero net force and constant velocity (terminal velocity).

2. What happens to terminal velocity if the viscosity of the liquid doubles?

Since [v_t ∝ \dfrac{1}{η}], if viscosity doubles, terminal velocity becomes half.

3. How does the radius of a sphere affect its terminal velocity?

[v_t ∝ r^2]; doubling the radius increases terminal velocity fourfold.

4. Why do small oil droplets remain suspended in air for long durations?

Because their radius is very small, giving extremely low terminal velocity — they fall very slowly.

5. Can terminal velocity exist in a non-viscous fluid?

No. Without viscosity, there’s no resistive drag, so the object continues accelerating.

6. Why is terminal velocity higher in air than in water?

Air has much lower viscosity than water, so resistance is smaller, giving higher terminal velocity.

7. What happens to terminal velocity if fluid density increases?

Since [v_t ∝ (ρ_s – ρ)], terminal velocity decreases as fluid density increases.

8. Why does a steel ball fall faster than a wooden ball of the same size in water?

Because the density difference [(ρ_s – ρ)] is greater for steel than wood, giving larger terminal velocity.

9. What is the effect of gravity on terminal velocity?

Terminal velocity increases directly with [g]; higher gravitational acceleration gives higher [v_t].

10. How can you experimentally determine terminal velocity?

By dropping a small sphere in a tall liquid column and measuring its steady fall speed after a certain distance.

11. Why does a raindrop not hurt despite falling from kilometers above?

It quickly reaches terminal velocity (≈ 10 m/s) due to air resistance, so it doesn’t accelerate indefinitely.

12. Does terminal velocity depend on shape?

Yes, the constant in the drag expression (6πrηv) depends on geometry; irregular shapes alter drag and terminal speed.

13. What if the fluid temperature increases?

Viscosity decreases with temperature, increasing [v_t].

14. Why does honey exhibit smaller terminal velocity than water?

Honey has much higher viscosity, offering more resistance to motion.

15. What would happen if buoyant force were neglected in calculations?

The calculated [v_t] would be slightly higher, since buoyancy always opposes weight.

7. FAQ / Common Misconceptions

1. Is terminal velocity the maximum possible velocity in all media?

No, it applies only in viscous media where drag balances weight. In vacuum, there’s no terminal velocity.

2. Does larger mass always mean higher terminal velocity?

Not always; terminal velocity depends on radius, not just mass.

3. Why doesn’t a feather reach terminal velocity like a ball?

It does — but because of its large area and low density, the terminal velocity is very small.

4. Is terminal velocity constant for all spheres?

No. It depends on [r], [η], and [(ρ_s – ρ)].

5. Does terminal velocity depend on initial velocity?

No. Regardless of initial speed, the object will eventually reach the same terminal velocity.

6. Can terminal velocity be zero?

Only if the object’s density equals the fluid’s density — it will neither rise nor fall.

7. Why do bubbles rise faster in warm water?

Warm water has lower viscosity, so terminal velocity increases.

8. What happens to [v_t] if the radius of the sphere is halved?

[v_t] becomes one-fourth.

9. Why does a skydiver open a parachute?

To increase effective area and drag, reducing terminal velocity for a safe landing.

10. Is terminal velocity achieved instantly?

No, it’s reached gradually as acceleration decreases to zero.

8. Practice Questions (with Step-by-Step Solutions)

Q1. A steel ball of radius [1 mm] falls through glycerine ([η = 0.83 Ns/m²], [ρ = 1260 kg/m³]). Find terminal velocity if [ρ_s = 8000 kg/m³].

Solution:

Using [v_t] [= \dfrac{2r^2(ρ_s – ρ)g}{9η}]

[v_t] [= \dfrac{2(1×10^{-3})^2(8000 – 1260)×9.8}{9×0.83}]

[v_t] [= 0.017 m/s]

Q2. By what factor will terminal velocity change if the radius doubles?

Solution:

Since [v_t ∝ r^2], if radius doubles, [v_t] becomes 4 times larger.

Q3. If viscosity of the fluid becomes 3 times, how does [v_t] change?

Solution:

[v_t ∝ \dfrac{1}{η}], so terminal velocity becomes one-third.

Q4. Two spheres of same density fall through water. The radius of one is twice the other. Find ratio of terminal velocities.

Solution:

[\dfrac{v_1}{v_2}] [= \left(\dfrac{r_1}{r_2}\right)^2] [= (2)^2 = 4 : 1]

Q5. A glass bead and an air bubble of same radius rise/fall through water. Which has higher terminal velocity?

Solution:

For the bead, [(ρ_s – ρ)] is positive and large → higher [v_t].

For the bubble, [(ρ_s – ρ)] is negative and small → lower [v_t].

Hence, the bead has higher terminal velocity.