Physics and Mathematics

Theorem of Perpendicular Axis

1. Introduction

The Theorem of Perpendicular Axes applies to planar (2D) bodies such as discs, rings, or laminae.

It establishes a relationship between the moment of inertia of a body about two perpendicular axes in the plane and a third axis perpendicular to that plane.

2. Statement of the Theorem

If a plane lamina lies in the XY-plane, then the moment of inertia about the perpendicular Z-axis (passing through the point of intersection of X and Y axes) is equal to the sum of the moments of inertia about the X and Y axes.

[

I_Z = I_X + I_Y

]

where:

- [ I_Z ] = Moment of inertia about the Z-axis (perpendicular to the plane)

- [ I_X ] = Moment of inertia about the X-axis (in the plane)

- [ I_Y ] = Moment of inertia about the Y-axis (in the plane)

3. Derivation

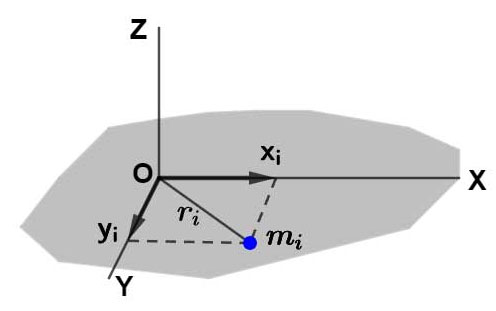

Let the lamina consist of many small particles, each of mass [ m_i ] at coordinates [ (x_i, y_i) ] in the XY-plane.

- Distance of the particle from the X-axis = [ y_i ]

- Distance of the particle from the Y-axis = [ x_i ]

- Distance of the particle from the Z-axis = [ r_i = \sqrt{x_i^2 + y_i^2} ]

Then,

[

I_Z = \sum m_i r_i^2 = \sum m_i (x_i^2 + y_i^2)

]

Expanding:

[

I_Z = \sum m_i x_i^2 + \sum m_i y_i^2

]

Hence,

[

I_Z = I_X + I_Y

]

Thus, the theorem of perpendicular axes is proved.

4. Conditions of Applicability

- The theorem is valid only for plane (2D) laminae.

- The three axes must be mutually perpendicular, and the Z-axis must be normal to the plane.

- The intersection point of the axes must pass through the same point (usually the center).

5. Key Features

- Simplifies finding [ I_Z ] for planar objects when [ I_X ] and [ I_Y ] are known.

- Used for symmetrical laminae like discs, rings, rectangles, etc.

- Useful in deriving expressions for moment of inertia of circular or polygonal objects.

- Not valid for 3D objects such as spheres or cylinders.

6. Important Formulas to Remember

| Quantity | Formula | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Theorem of perpendicular axes | [ I_Z = I_X + I_Y ] | For lamina lying in XY-plane |

| Moment of inertia of element | [ I = \sum m_i r_i^2 ] | Definition for discrete particles |

| For continuous body | [ I = \int r^2 , dm ] | Integral form |

| Distance relation | [ r^2 = x^2 + y^2 ] | Pythagoras relation for planar lamina |

7. Conceptual Questions

1. For what kind of bodies does the theorem of perpendicular axes hold?

It is valid only for flat (planar) bodies such as laminae, discs, or rings.

2. Can the theorem be applied to a sphere?

No, it cannot. The theorem applies only to two-dimensional laminae.

3. What does [ I_Z = I_X + I_Y ] physically represent?

It shows that rotation about the perpendicular axis involves both X and Y planar distributions of mass.

4. Does this theorem depend on the origin’s position?

Yes, all three axes (X, Y, and Z) must intersect at the same point for the theorem to hold.

5. How is this theorem useful for a circular disc?

It helps in determining [ I_Z ] about the center, since the disc is symmetric and [ I_X = I_Y = \dfrac{1}{4}MR^2 ].

6. What will be [ I_Z ] for a circular disc?

[ I_Z = I_X + I_Y = \dfrac{1}{4}MR^2 + \dfrac{1}{4}MR^2 = \dfrac{1}{2}MR^2 ].

7. Why must the axes be mutually perpendicular?

Because only then can their respective perpendicular distances combine vectorially using [ r^2 = x^2 + y^2 ].

8. Can the theorem be extended to more than three axes?

No, it applies specifically to three mutually perpendicular axes at a common point.

9. Does this theorem have a 3D analogue?

No, but it complements the **Parallel Axis Theorem** in 3D calculations.

10. Is the theorem valid for non-homogeneous bodies?

Yes, as long as the body is planar and the axes meet the theorem’s conditions.

8. FAQ / Common Misconceptions

1. Can we apply the perpendicular axis theorem to any object?

No, it’s valid only for **planar (2D)** laminae, not for solid 3D bodies.

2. If the axes don’t meet at a single point, can we still use the theorem?

No, all axes must intersect at the **same point** for the theorem to hold.

3. Does the theorem depend on mass symmetry?

No, it’s valid for all planar distributions, whether symmetric or not.

4. Is [ I_Z = I_X + I_Y ] always true in any coordinate system?

Only if the coordinate axes satisfy the conditions of the theorem (planar lamina and common intersection point).

5. Can the theorem be used to derive [ I = \dfrac{1}{2}MR^2 ] for a disc?

Yes, it is directly used for that derivation by taking [ I_X = I_Y = \dfrac{1}{4}MR^2 ].